|

1. The Beginning of Studies on Kalasasaya

|

|

Since

the most important part of this work is that which has to do with the

great Temple of the Sun,

Kalasasaya, and the applied science possessed by American man,

we believe it fitting to review the laborious preparatory stages of

these studies which in all their ramifications, lasted more than a third

of a century and the quintessence of which is found in the present

chapter of the second volume of

TIHUANACU, THE CRADLE OF AMERICAN MAN. We shall first present a special bibliographic analysis related to the material.

We do not propose to mention here what

chroniclers and travelers have said on the subject. Neither do we wish

to scrutinize the works which modern laymen have devoted to the subject.

Rather, we wish only to refer to the works of authorized persons which,

not having lost their timeliness, have an important relation to that

supreme monument and the science which American man left us with it.

With respect to the works of chroniclers and travelers, as well as those

of dilettantes, we have set aside a bibliographical section at the end

of the last volume, accompanied with brief comments.

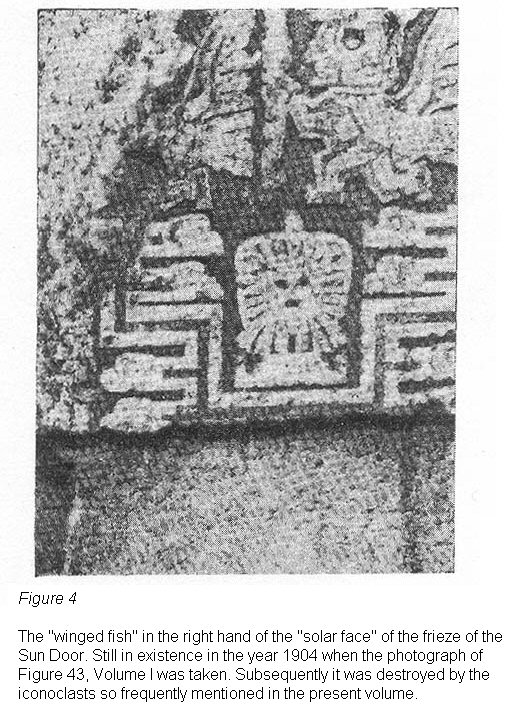

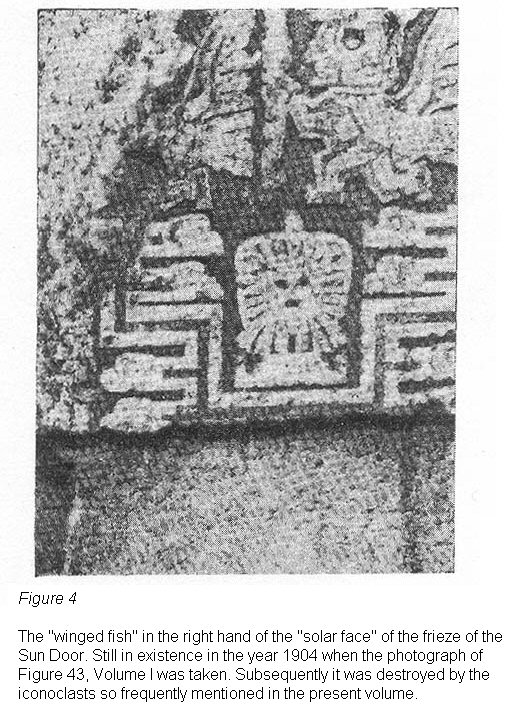

It was in the year 1904 that we began our work directed toward the discovery of the secrets held by

Kalasasaya and the Sun Door, its principal stone piece.

In an elemental manner, from the point of view of the engineer, we first

drew a map of the ruins and took detailed photographs of the monuments

on large plates. This course was followed in view of the fact that a few

years before there had begun, in systematic form, the destruction of

the magnificent ruins of

Tihuanacu; a destruction carried out both by the builders of

the Guaqui-La Paz railroad and the Indian contingent of the modern

village of Tihuanacu who used the ruins as a quarry for commercial

exploitation.

In view of this fact, and in order to

avoid their irreparable loss to Americanistic science and future

civilization and culture, the author proposed to save what still

remained. He struggled tenaciously along

Don Manuel Vicente Ballivián, President of the Geographic

Society of La Paz, and succeeded in having the Congress pass laws for

the protection of the archaeological monuments on Bolivian soil. This

program of protection was put in the hands of the State, which did not

carry out the laws nor oblige any one else to do so, with the result

that the vandalic destruction continued unpunished. We have preserved a

full graphic and literal documentation on this subject and we recall

that certain newspapers, which waged an ignoble campaign against us,

even went so far as to encourage the destruction of those archaeological

relics.

In order to arouse the interest of the

scientific world, especially of America, the author presented in 1908,

before the Pan American Scientific Congress, meeting in Santiago de

Chile, an extensive work, rather fully

documented but of relative value, which was published in Vol. I of the

"Anales" (Anthropological Section) pp. 1 to 142, with illustrations, maps, facsimiles and a chromolithograph.

We continued our work on the site of

our studies, whenever our professional occupations and the routine

struggle for existence permitted, and in the year 1910, as the delegate

of Bolivia to the Twentieth International Congress of Americanists in

Buenos Aires, we gave an account of the new discoveries and studies

carried out at

Tihuanacu, by means of an extensive lecture illustrated with

maps and some one hundred slides. Those attending the Congress were then

invited, in the name of the government of Bolivia and the President of

the Geographic Society of La Paz, Mr. Manuel Vicente Ballivián, to

visit those amazing American monuments.

A considerable section of the Congress

accepted this invitation, and thus began the trip across the continent

on the Argentinian railroads, in wagons, on the backs of animals, and

finally on the recently constructed Bolivian railways. A lecture

delivered by the author at the scene of the ruins gave rise to a lively

discussion, and attracted the attention of scientists to Tihuanacu. At

that time, we pointed out the basis of the efforts to investigate the

age of Tihuanacu by means of astronomical calculations in the Temple of

the Sun, Kalasasaya. As was to be supposed, in view of the fact that

none of those present had technical knowledge of such complicated

material, that preliminary study was received with a certain amount of

scepticism. On this occasion there was distributed among the delegates

to the Congress, a voluminous photographic album and book dealing with

the ruins, written by Don Manuel Vicente Ballivián and the present

author.

After many articles of scientific

divulgation published both in the country and outside, there appeared in

La Paz, in 1912, the book entitled "Guía General llustrada. Tihuanacu, Islas del Sol y de la Luna, etc."

We left the copy for this book in press upon going to travel in Europe

with the object of amplifying our studies, a circumstance which made it

impossible for us to check personally the correction of the proofs. As a

result, a good many typographical errors slipped in, especially in that

part dealing with ideas on the chronology of

Kalasasaya, where the compositor left out two lines. This caused José Imbelloni, in 1926, to emit certain derogatory opinions in his "Esfinge Indiana",

pretending maliciously not to be familiar with our later studies on the

age of Tihuanacu. The "lapsus tipograficus" in question was corrected

in the "Comentario de la Esfinge Indiana", La Paz, 1927.

The "Guía de Tihuanacu" was an

amplification of the essay which we presented in 1908 before the

Scientific Congress meeting in Santiago de Chile, in which there was

attacked, in the form of an "Arbeitshipotese",

(53) the question of the age of Tihuanacu --- but naturally only in the form of a preliminary essay.

After remaining in Europe for two

years, during which time the author devoted himself to the study of

natural and geodetic sciences as well as other scientific studies, there

appeared in Germany and other countries in 1914, the first volume of "Una Metrópoli Prehistórica en la América del Sur", which contained the first studies connected with the building of

Kalasasaya.

The years passed and in spite of the

fact that the struggle for existence absorbed the major part of our

time, we continued dedicated to the task of developing our astronomical

studies, and to carrying out serious geodetic investigations and

astronomical calculations in Tihuanacu. Finally, in the year 1918, we

published a work connected with the determination of the age of

Tihuanacu, entitled "El Gran Templo del Sol en los Andes. La Edad de Tihuanacu", which appeared in "Bulletin No. 45" of the Geographic Society of La Paz.

During the following years we drew up exact maps of the region of

Tihuanacu and of all the monuments, especially of Kalasasaya, all of which are published in the present volume.

In August, 1924, the author, as the

delegate to the Twenty-first International Congress of Americanists held

in The Hague, gave an account of the new investigations carried out in

the prehistoric city, by means of an illustrated lecture using the

prepared maps. This was later published in the "Anales" of this Congress.

Later, the same subject was treated in a lengthy disquisition,

followed by an exhibition of materials and slides, in the astronomical

observatories of Potsdam and Treptow (in Berlin). An extract from this

lecture was published in the "Weltall", the journal of the latter organization.

As a result of our instigations brought forward during the conference at The Hague,

(54) a trip to Bolivia was arranged by the Director of the Astronomical Observatory of Potsdam,

Dr. Hanns Ludendorff, by the astronomers Professor Dr. Arnold Kohlschütter, of the University of Bonn,

Dr. Rolf Müller, of the Astrophysical Institute of Potsdam and

Dr. Friedrich Becker, of the Specula Vaticana, with the object

of carrying out astrographic studies in the southern firmament and with

the further purpose of checking the astronomic-archaeological

investigations of the author in Tihuanacu. They were with us during the

years 1927 to 1930; they visited Tihuanacu for a considerable period of

time and in this interim carried out new and profound observations of

unquestionable accuracy.

Among the members of the mission, Dr. Rolf Müller

dedicated himself more earnestly than any other investigator to

observations in Tihuanacu; he remained a long time at the ruins,

carrying out confirmatory work in connection with our previous studies

and making new investigations of great importance. This task was

completed between the years 1928 and 1930. After a new determination in

the solstice of June, 1928, an official record was made of the

preliminary work which, accompanied by a brief review from the pen of

the author, was sent to the Twenty-third Congress of Americanists which

met that year in New York City. The record and review were published in

the "Anales" of this Congress but unfortunately, with some typographical errors.

(54a)

We continued the

astronomical-archaeological investigations with Professor Müller, not

only in the ruins of Tihuanacu and in the South of Peru, but also in La

Paz; the early results of this research were later published by

Professor Müller in a "Report" in German. At the express

desire of the author, we translated the original manuscript of the

report to Spanish, so that it could be published in the "Boletín de la Sociedad Geográfica de la Paz", At that time, unfortunately, the publication of that "Boletín" was suspended and we had to insert the work in the "Anales de la Sociedad Científica de Bolivia".

Upon his return to Germany, Professor

Müller, being aided by the valuable cooperation and advice of the

learned Professor Dr. Hanns Ludendorff, published a detailed work on our

investigations in Vol. XIV of the "Baesler Archiv", pp.123-142.

(55)

What has been related above,

constitutes the genesis of the work carried out in the Temple of the

Sun, Kalasasaya. It is natural that this work should have attracted the

attention of the scientific and pseudo-scientific world, but since it is

a question of so complex a subject, there were no persons competent to

judge those investigations with their own criteria.

Finally in the year 1926 there appeared a book with the bombastic title "La Esfinge Indiana", written by

José Imbelloni, of Buenos Aires, a good man but completely

devoid of scientific training. His work is an amorphous conglomeration

of Americanist material in which, on the basis of childish arguments, he

criticizes our investigations in Kalasasaya, especially those dealing

with the age of Tihuanacu. It was an easy matter for us to refute the

scatterbrained criticisms of the "scholar" Imbelloni, in a brochure

entitled "Comentario a la Esfinge Indiana" and in articles published in the Sunday editions of "La Nación" of Buenos Aires; with this we thought we had ended the matter.

However, Dr. Müller, who had received

this criticism, which is really a "Sphinx" as its name indicates, also

alluded to it in his work "El Concepto Astronómico del Gran Templo del Sol de Kalasasaya",

and among other things, said the following: "As I have stated in the

introduction, Professor Posnahsky has concerned himself with that

problem. In1926 there was published in the Argentine Republic a

voluminous book by

José Imbelloni, which, among other things, also deals with the

culture of the inhabitants of the Andes of South America and in which

the author refers to the determination of the age of Tihuanacu by

astronomical means.

Imbelloni criticizes severely Professor Posnansky's

work in this connection and affirms that all of the calculations of the

said Professor are absurd and untenable. If indeed, as is the case,

there is some room for criticism in the first works of Professor

Posnansky in the year 1912, in view of the fact that these were nothing

more than his first attempt in astronomical problems and in which he

used the astronomical point of view only in the form of an

"Arbeitshipotese",

(55a) there is no reason to so designate them.

Imbelloni maliciously ignores the later works of

Professor Posnansky of the years 1918, 1924 and following. If a

person like Imbelloni, is going to concern himself with astronomical

questions, which, in his book he calls "elemental, simple and known", he

should at least study these sciences, and then he would not have been

guilty of such injudicious statements and mistakes, which in truth

concern elemental ideas, as for example, that of confusing the precession of the equinoxes with the variation of the obliquity of the ecliptic.

But his situation is even worse in regard to his mathematical

calculations and especially when he cites examples based on his

criterion, with which he wishes to prove supposed absurdities in

Professor Posnansky.

For example: Imbelloni

(56)

calculates the dimensions of the length of the walls of the Temple (in

which operation he makes a mistake in the length of the Temple) and

uses, instead of the figure 129 m., the figure 135 m., which corresponds

to the Temple of the second Period plus the Balcony of the Third

Period. The value that Imbelloni obtains by this method sui generis, is then compared with the present obliquity of the ecliptic; of course without even taking into account the "influence of the polar altitude".

If Imbelloni had made his calculations in the correct form, or,

applying the influence of the altitude of the pole which is 2° 10' then

he would have obtained the following absurd results: that Tihuanacu

could have been constructed some thousands of years

"post-Christum natum !!"

After the foregoing quotation from Professor Müller, we shall file

Imbelloni and his "science."

Returning to our subject, we wish to

point out that after the astronomical mission had returned to Europe, we

continued our studies and obtained new material, the results of which

we will state briefly in this chapter. We shall refrain from going into

greater detail in order not to convert it into a special monograph.

However, for those who have a special interest in this matter, we

recommend the publications of Dr. Müller our companion in investigations

during the years 1928 to 1930. These publications constitute the most

serious and authoritative treatment that has been given this subject,

from an astronomical point of view.

Since it would be troublesome to repeat

the already published data --- a great part of which was perhaps

rectified by the new studies carried out in company with Dr. Müller ---

we are, in the present chapter giving only a synthesis of the results

ultimately obtained, or those definitively rectified.

|

(53)

"Arbeitshipotese". A technical German word which expresses the idea

that a scholar takes as a basis a hypothesis which will serve as an

advance background for an investigation which is in a state of

preparation.

(54) Anales del Congreso Internacional de Americanistas, The Hague, p. 60.

(54a) In the copy of the New York Public Library we have rectified these errors.

(55) Dr. Müller corrected, in the

"Report" published in the Baeiler Arcbiv, certain points of his work

printed in the Anales de la Sociedad Científica de Bolivia.

(55a) See Note 53.

(56) Imbelloni was never in Tihuanacu.

|

|

|

|

Back |

|

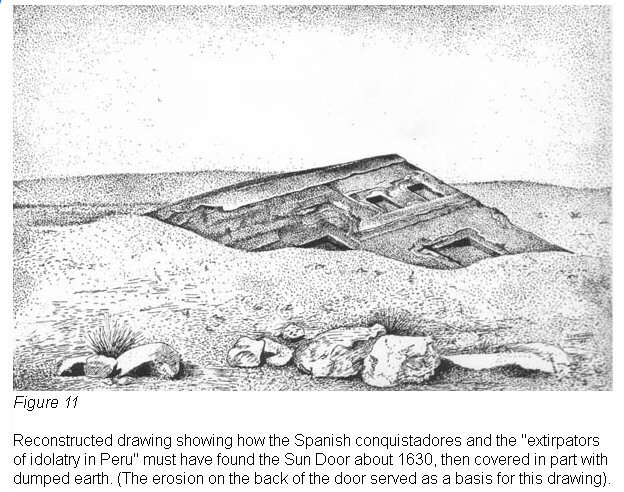

2. Architecnographical Introduction

|

|

After having discussed the inscriptions of the

Sun Door in great detail in

Chapter I, we repeat that all that is nothing more than the description of the calendigraphic functions of the building of

Kalasasaya. Since we treated this

very briefly in Vol. I, we shall begin in the present chapter to discuss

extensively this magnificent solar observatory called by the present inhabitant

of Tihuanacu "Kalasasaya", which as has been explained before, means

nothing more than "standing stones."

Its geographic location is 16° 34' 54" latitude south and 4 hours 35'

18" west of Greenwich.

The ancient and true name of this "solar temple" is unknown at the

present time. However, not only in Peru but also in Bolivia, there are many

locations which without doubt, served as solar observatories and which now still

preserve the name of "Inti-huatana" in Keshua and "Inti-tshintaña"

in Aymara, the translation of which would be: "Hitching Post of the Sun".

Also there is the name "Lukurmata",

(57) which is also that

of a place indisputably that of a solar observatory located south of Titicaca.

Even after the Conquest, the aborigines concerned themselves with observing

the celestial movements, as we shall see farther on, especially the solstices, which they called "Willakuti"

(58) and the equinoxes. It is very possible that in the epoch of the apogee of

Tihuanacu, when the sacerdotal caste was made up of the noble tribe of the

Khollas, who spoke Aymara, the solar temples had some significant name and

especially this building, the most important of Tihuanacu.

In this monument, which like everything in that city is incomplete, there can be

noted unquestionably the existence of two periods in which it was erected. These

periods, of course, are separated by a considerable chronological space of time.

Before considering the details of the matter, it is necessary to present a brief

architecnographical introduction, even though the maps intercalated in this

chapter are so clear that they scarcely need any further comment.

As is seen in the first volume (Pg. 66), there are various levels in the ground

of Tihuanacu, or rather it is built on terraces of different heights, as was

demanded by the whole of this great city of temples and gardens and the

architectonic purpose and arrangement of each building. In the above drawing,

one can note that the external floor of Kalasasaya was that from which arose the

perron which gives access on the east to that great Temple of the Sun. As the

main floor of the interior of the temple, it can be considered the level of the

superior platform of the perron. However, in that same interior of the

observatory there exists another small temple or "sanctum sanctorum",

though it belongs to a later period, the period of glory (the Third Period of Tihuanacu). There are still other levels, some higher than that of the platform

of the perron, and others lower, as we shall see farther on.

It is thus that the Temple of the Sun was built on an artificial terrace

supported by two other exterior ones, giving Kalasasaya in its time an

appearance in its base something like that of a step-like pyramid. I repeat,

that there were apparently two exterior terraces both supported by walls, as is

shown by their remains, especially outside the east and north walls. To the

west, it seems that they had not planned the construction of terraces, because

the building was joined intimately with what is called the "Palace of the

Sarcophaguses" and various subterranean rooms which we shall discuss in due

course. Neither were there terraces to the south, or at least there are no

traces of them at this time.

Certainly, the building communicated by means of a platform with the "Pukara

Akapana". It would not be at all impossible, by means of a serious

excavation on this site, to discover indications of a communication between both

monuments, about which mention is made in a tradition among the oldest

inhabitants of the village. With regard to the north wall, the terraces are in

evidence with the ruined remains of the walls.

All of the work of investigation was seriously hampered by a lack of the

elements of a superstructure and to some extent of an infrastructure, in the

different buildings, as well as by a lack of architectonic elements. Like all

the other buildings of Tihuanacu, it was destroyed at the beginning of the

seventeenth century by the zealous priest of the locality, Pedro de

Castillo.

Guided by a blind faith, commendable from his point of view, he destroyed the

most noteworthy and precious part of the magnificent city, and constructed the

enormous temple to the new faith on the same spot where this city rose.

Perhaps a portion equal to that destroyed by this cleric and his follower, the

truly responsible agent in the destruction, the Indian chief Paxi-pati,

(59) has

been that devastated by the builders of the railroad to Guaqui, and as we

pointed out in the first volume, they were not even strangers !

(60) Such

destruction continues until the present time at the hands of irresponsible

inhabitants of the place, in spite of our continual complaints before the

national government.

On the basis of surveyings --- the most careful that it was possible to make ---

without official or any other sort of aid, we have perhaps succeeded in giving

an approximate idea of what Tihuanacu was in the period of its greatest glory.

In the various maps which accompany these lines, not only scholars, but those

who some day may make serious excavations in those places, will find a moderate

basis for their labors. If indeed there is still considerable to be described in

Tihuanacu, the principal part of it lies on the surface.

This is the

documentation to be extracted from the enormous amount of material employed in the

construction of churches, country houses and city dwellings near the ruins,

nearby villages and even in the city of La Paz itself. Let us cease lamenting

what happened, for which there is now no remedy, but let us not cease

recommending to the Bolivian people a greater respect and regard for these

magnificent remains of past American splendor. This should be implemented by the

creation of a great National Park, the center of which would be these extremely

old testimonies to the labor and science of American Man, the most important,

perhaps, for the study of human civilization.

|

(57) "Lukurmata" is an

agglutination of "Loka-Uru-Ymata" which translated would be

"Measure-Day-Observed", or a calendar; it may well be that the stone

calendar "Kalasasaya" had this name.

(58) Cf. Vocabulario of Ludovico

Bertonio, Juli Pueblo, 1612.

(59) In gratitude for the

accomplishment of having destroyed the most magnificent monuments of his

forebears, the cleric (the painter of the pictures in the church of Tihuanacu)

placed at the end of one of these, the picture of the Indian chief with the face

of a noble Kholla, beside his wife, who has the somatic appearance of a half-breed.

(Chromo, Fig. 12).

(60) In the construction of this

railroad, carried out by the government, there participated only national

technicians and workers. The chief of construction operations was the Peruvian

engineer, Mariano Bustamante.

|

|

|

|

Back |

|

3. The Object of the Building Kalasasaya

|

|

Before entering into a detailed discussion of the construction of the Temple

of the Sun, it is necessary to brush aside the veil of ignorance which until now

has covered the purpose of its construction and its importance for the life,

economy and religion of the people of that distant period.

As is well known, the great Andean population and that of the nearby regions,

was composed in the greater part of farmers and herdsmen (there also existed

tribes which devoted themselves exclusively to fishing), and Tihuanacu was the

religious and cultural nucleus. The population was extremely dense, as serious

studies in this respect show.

Thus it resulted that the agricultural and cattle

production of a relatively small region had to provide the support for

considerable masses of individuals and so the country was cultivated in an

intense way, as we shall see farther on. A bad agricultural year brought famine,

discontent, social disturbances and the consequent discredit of the dominant

castes. It is also known, even by the person most ignorant of agronomy, that to

obtain good harvests and abundant issue in cattle, an exact knowledge of the

calendar is necessary. The different seasons and the right times for plowing the

fields must be determined, as well as the corresponding seasons for the sowing

of certain crops, and the exact moment for breeding various types of cattle.

Of

course, the man who is a product of modern culture, and who has an

almanac, can

scarcely appreciate the importance in that epoch, of possessing exact

calendarian knowledge. In order to obtain this data, it was necessary

for the

castes who ruled the people, to obtain an exact astronomical knowledge,

and

consequently this science played a highly important role in the most

civilized

zone of the continent even in that distant period. The great Altiplano,

locked

between the Andes, was covered then to a great extent by water from

which

protruded extensive islands and peninsulas. The smallest span of land

was

utilized by means of "agricultural terraces".

Consequently, the

observation of the phenomena which took place in the firmament, especially

certain knowledge about celestial mechanics, was indispensable for the Khollas,

the sacerdotal caste, in order to provide their subjects with good crops and, as

a result, social tranquility and the prestige necessary for the fulfillment of

their mission. Consequently, astronomy had not only a religious, but also an

essentially practical and social basis. The priests or "Willkas", as

they were certainly called, wielded over their subjects, those sail half-savage

hordes, spiritual and divine power in addition to their earthly authority. It

was thus necessary for them to indicate, not only such agricultural dates as

were necessary for irrigation, the breeding of animals, fishing, etc., but also

those of the many feast days connected with the seasons and subdivisions of the

year.

With the aid of this brief introduction, it will be appreciated that

Kalasasaya

was something more important than a simple temple of the Sun; it was an Almanac

of carved stone, as we shall see farther on, with which there were determined,

in a mathematical manner, the different seasons and subdivisions of the year.

THESE CALCULATIONS WERE ONLY POSSIBLE BY MEANS OF A BUILDING LOCATED EXACTLY ON

THE MERIDIAN AND THE LENGTH AND WIDTH OF WHICH CONFORMED TO THE MAXIMUM ANGLE OF

SOLAR DECLINATION BETWEEN THE TWO SOLSTICES. |

| |

|

|

|

Back |

|

4. The Two Different Periods in the Construction of Kalasasaya

|

|

As is established in the corresponding chapter of the first volume, there are

THREE PRINCIPAL PERIODS in Tihuanacu. One, extremely primitive and with its own

characteristic features, to which there belongs, as a building exclusively of

that period, the "Palace" or "Temple" marked "C"

on the triangulation map of Tihuanacu inserted in that volume, (Plate 3). In

this period there was also begun the "Pukara" or fortress of Akapana

and the Temple of the Moon, today called Puma-Punku. The three works have the

same orientation, or are 2° 49' 7" from the meridian. We have very little

knowledge of that period because of its great age.

(61)

The construction of the Pukara Akapana and the Temple of the Moon,

Puma-Punku,

was continued in the Second and Third Periods of Tihuanacu. We possess ample

material with which to elaborate our knowledge of these two periods and

especially in order to understand, in addition to many other things, the system

and method of their constructions, their science, their cosmological beliefs and

theogonic ideas.

In Kalasasaya there can be noted the instructive evidences of both cultures

which, we repeat, are separated by a long lapse of time. To the Second Period

there belongs, without any doubt, the great quadrilateral, for the erection and

architecture of which they seem to have taken their inspiration from the small

temple of the First Period . . . AFTER HAVING EXCAVATED IT. Kalasasaya of the

Second Period is 128 meters 74 centimeters long by 118 meters 26 centimeters

wide. The monumental perron to the east belongs to this period.

(62)

We assign to the Third Period, without fear of error, the monumental colonnade

or balcony wall, and another building which is within the great enclosure beyond

the stair which we have designated provisionally "sanctum sanctorum",

as well as the REPAIRS MADE ON THE EAST WALL which itself belongs, without

doubt, to the Second Period. It should be kept in mind that in this period there

existed, possibly on the same site, a balcony wall, doubtless of red sandstone,

with the object of protecting from the view of strangers the observation post

which was found at the center of the line between the southeast and northeast

pillars. In the course of this chapter unimpeachable proof of what we have just

affirmed in this paragraph will be supplied.

During the First Period sandstone which comes from the mountainous region to the

south of the ruins, was used exclusively; there was also used for certain works

(sculptures of heads to be set in the walls) a soft calcareous tufa.

In the Second Period there was used, although on a small scale, the extremely hard, eruptive-crystalline rocks like the

andesites. Naturally, they used sandstone when it belonged to the preceding

period and was already placed and cut. They then arranged it, retouched it and

continued the former work according to their own criterion, with their new style

and symbolic decoration. An eloquent example illustrating the improvement of

previous works, is the retouching of the colossal idol which they found

in the temple of the First Period.

This, roughly carved, was given a new form

and was covered with the symbolic inscriptions of the new epoch. Another most

impressive example is to be observed in Puma-Punku, the construction of which

was continued in the Second and Third Periods in a very active form.

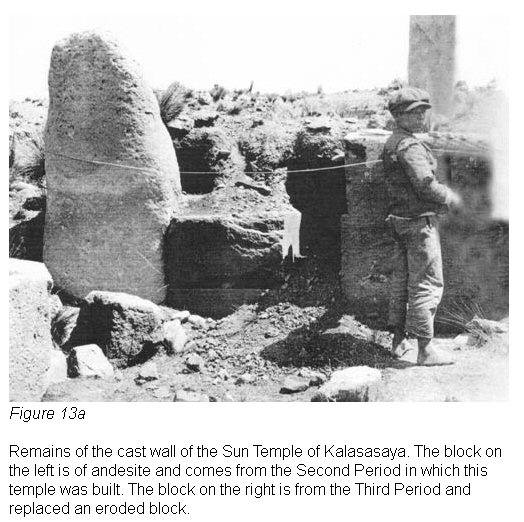

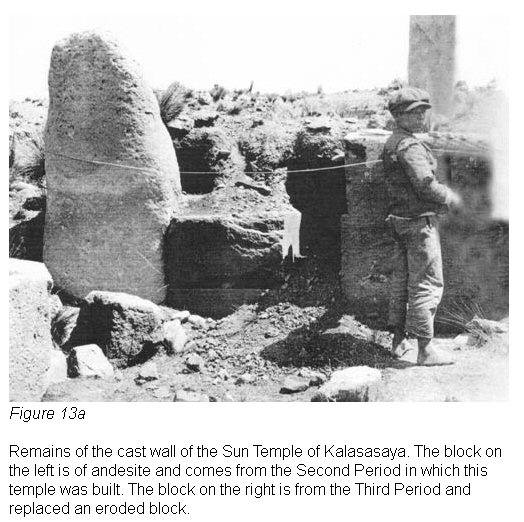

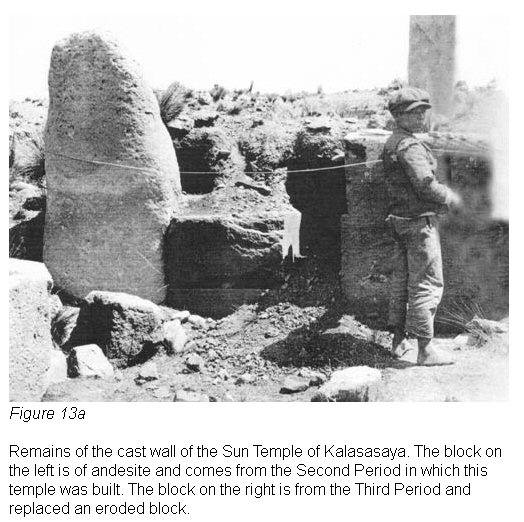

The south, west and north walls (let us say the walls of less rank) belonging to

the Second Period of Kalasasaya, are still of red sandstone.

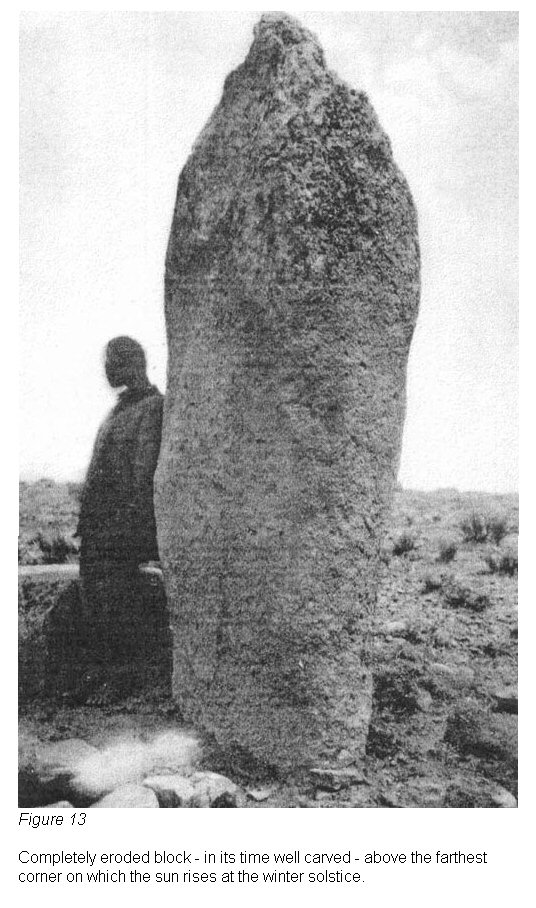

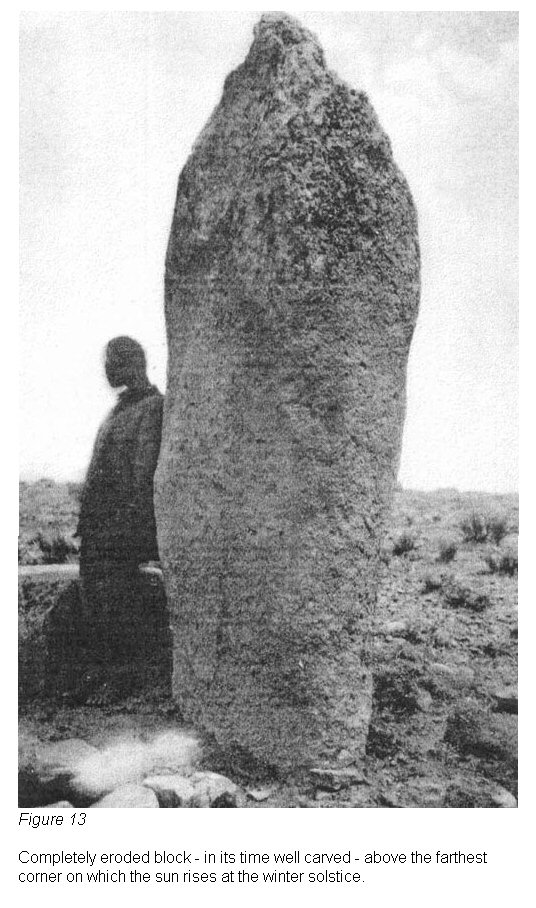

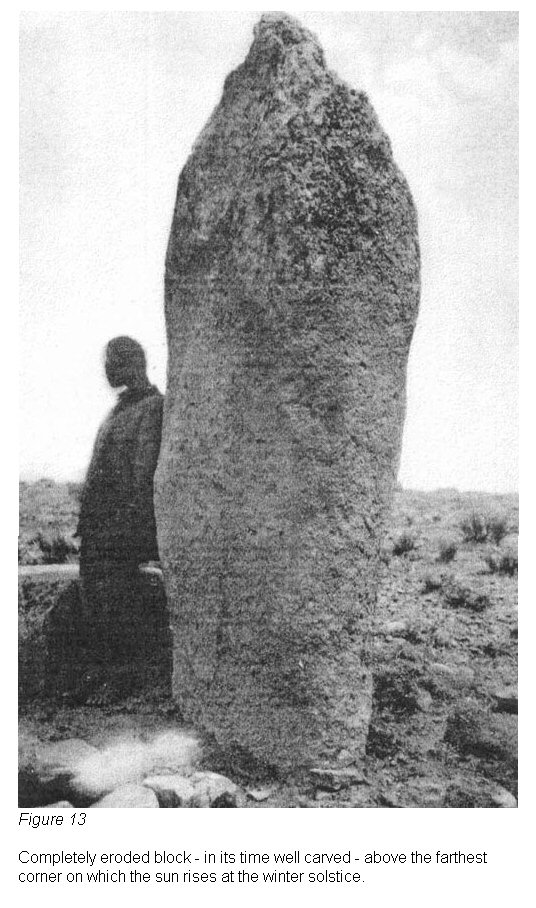

The east wall, or

that of great rank and also of the Second Period was already constructed of

igneous, andesitic rocks. (See an enormous abrasion in

Fig. 13, 13a, 13b

figs 13, 13a, 13b

All that which is still standing of the

Third Period in Kalasasaya is worked

exclusively in hard andesitic lava, as for example, the balcony wall, the

sanctissimum and the reconstructions of the Second Period. But it is not only in

the material that the Third Period differs from the preceding one; it is

especially in the so perfect working of the rock, a thing unsurpassed in the

world up to this time. It is seen further in the symbolic style of the

engravings which are extraordinarily advanced and especially, in the astronomical

orientation of its construction which shows a variation of 25' 30" between

one period and the other.

The orientation of the south wall of Kalasasaya of the Second Period is 89°

18', of the north 89° 20', of the east 358° 58' 30" and of the west 358°

53' 30". The constructions of the Third Period such as the sanctissimum and

the balcony wall, deviate from the meridian to the west 42', or they were

located at 359° 18'.

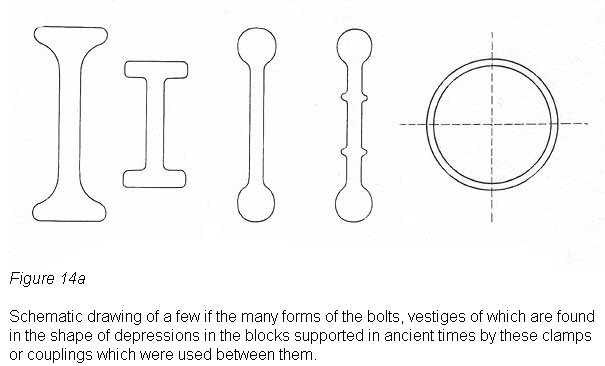

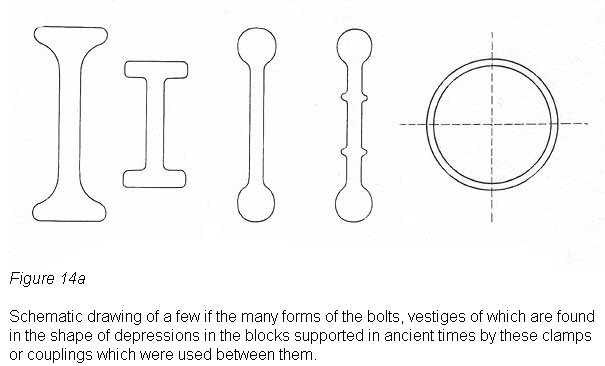

Bronze appears in the Third Period. One frequently notes the repairs in the

walls of former periods in which they joined blocks by means of bronze bolts;

these they used in different shapes for their own constructions, even in the

form of rings, fig 14.

fig 14

fig 14a

In this very period, characterized by a maximum

advance --- it constitutes the epopee of Tihuanacu --- the "Loka" also

appears, a common, everyday unit of measure which, to judge by the construction

of the balcony wall, had a length of 161 cm. 3.25 mm., equivalent possibly to

the arm span of the average individual of that time. (See our work: "Antropología

y Sociología").

The Sun Door is the most glorious monument of this period. An attempt was

made to finish the buildings of the First and Second Periods, as we shall see

farther on, especially the Temple of the Moon, Puma-punku and the

Pukara Akapana,

but they were not concluded. With the exception of the Temple of the First

Period, absolutely nothing is finished in Tihuanacu, not even the supreme piece

of this period, The Sun Door, as we have seen in the preceding chapter.

Tihuanacu of the Third Period is a megalomaniacal work like the Tower of Babel

and, had it been completed, it would possibly have surpassed everything that man

has constructed on the earth.

Among the sciences they came to know, as we shall see farther on, they mastered

the astronomical bearings of the meridian, with which it was possible to

determine the exact "amplitude" of the sun in the Third Period and

with this, in turn, the obliquity of the ecliptic --- a value which has supplied

us with the basis for determining the approximate age of Tihuanacu.

By means of

this knowledge the equinoxes and solstices were established, the aphelion and

the perihelion were known, the solar year divided into twelve months was used.

Even the zodiac became known, as has been seen in the previous chapter which

deals with the Sun Door, but in a form quite different from that known by the

ancient Semitic sages of Chaldea, whose knowledge was passed on to the astronomy

of the present day.

|

(61) Cf. in this connection: Posnansky,

Antropología y sociología de las razas interandinas y adyacentes,

p. 106; Isla Simillake y sus edificios, Las Paz, 1937.

(62) Later we shall give the exact

length of each one of the four walls, obtained by triangulation.

|

|

|

|

Back |

|

|

5. The Astronomic Science of Tihuanacu. How Kalasasaya was Built to be Used as a Stone Almanac

(Plan III)

|

|

As was pointed out in another section,

in order to construct the quadrilateral of Kalasasaya of the Second Period, with

the purpose of having this serve to determine the seasons of the solar year with

their subdivisions, it was necessary for it to have special form and

orientation, or for the east and west walls to be located exactly on the

meridian and especially, that the PROPORTION BETWEEN THE LENGTH AND WIDTH OF THE

BUILDING CONFORM TO THE MAXIMUM ANGLE OF SOLAR DECLINATION BETWEEN THE SOLSTICES

OF THAT TIME.

The problem was not a difficult one, as the careful observers of celestial

phenomena of that time, who were the priests and rulers, and who certainly

constituted special castes of Kholla stock,

(63) had preserved the traditions of

many centuries of observation and experience.

Neither is there the least doubt that before venturing to construct the great

Temple of the Sun, they had in Tihuanacu itself, or previously at some other

point of one of the large islands or peninsulas of the inter-Andean lake, an

adequate and prominent site with an horizon free of elevations and relatively

flat to the east, (64) (or perhaps a similar building on a smaller scale), in

which they obtained their great experience in making observations and

determining the dates of the year. In the construction of that primitive, or let

us say, trial solar temple, their knowledge was, without doubt, developed little

by little. They became familiar with the celestial phenomena, until they

attained the summum of learning to be able later to venture the construction of

this great Temple of the Sun of the Andes.

Possibly one of these trial

observatories was that of Lukurmata, which we discussed at the beginning of

subchapter "B."

Let us consider now what methods they used in the acquisition of this knowledge.

Since for these precise calculations they did not have at their disposal, as we

do, such instruments as theodolites, sextants, astronomical almanacs, etc., but

only sundials (65), plumbs, levels

(66) and topos

(67,67a) we are led to

wonder whether with such ordinary, though at the same time such efficient means,

they could carry out unquestionable celestial observations; this, of course,

from their anthropocentric point of view, in which they believed the earth to

be the center of the universe, around which all the celestial bodies moved, and

Tihuanacu the center of the earth, taking into account the age-old observations

of the atmospheric phenomena. It should not be forgotten that in very ancient

times not only the

residents of Tihuanacu made

astronomical observations of unquestionable value.

In China, 2,700 B. C, during

the reign of Wuwang in Lo Yang, they observed and determined the obliquity of

the ecliptic, measuring with a sundial nine feet high the shadows in the

solstices. The emperor Tschukong in the year 1100 B. C. measured the obliquity

of the ecliptic (68) and

Eratosthenes (born 276 B. C.) reckoned it at 23° 51'

15". (69)

Thus it is that China, Babylon and Chaldea gave to humanity the

celestial circle of 360° which we still preserve in our astronomical

measurements, atlantes, maps, geometry and all the calculations which have

angles as their basis.

Why then could the Tihuanacuans not have determined, during the solstices, the

line of the meridian on the basis of measurements of the corresponding shadows?

Why could they not have determined the solstices with their famous topos, taking

points of observation between marks on the horizon, which would indicate the

maximum oscillation of the sun toward the north and six months later toward the

south?

There are still many other primitive methods which they might have used

as a basis for determining the line of the meridian, knowing the amplitude of

the sun between the solstices. But there are also ordinary systems for obtaining

in a single night, with the primitive resources mentioned above --- which

without any doubt they had at their disposal --- the line of the meridian with

considerable accuracy. I shall present here a very eloquent example to show how,

through the culmination of some fixed star and with the ordinary resources we

have mentioned, they could have arrived at the line of the meridian.

They would have searched in the firmament toward the South Pole for a

circumpolar star; they would stretch a tape line more or less from east to west

(a line familiar to them since in the equinoxes they saw the sun rise and set on

that line) ; they would true the line with a level, Fig 15,

Fig 15

they would string

on this two small perforated discs of stone or wood; they would place a block of

stone or adobe in front of the tape line and on it an observation topo (sight).

The priest-observer, would kneel in front of the topo and wait until the

star passed the line on the left "toward the top" and he would instruct his assistant to move the small disc of wood

to the spot where the star passed through the line; they would then have

waited some hours until the star had culminated and again passed through

the line "downward" so that the assistant could place the second disc

in the corresponding location.

They would wait until daytime and then would

divide the space between the two discs in half, from which they dropped a plumb

to the ground. Then they would take another line with which they could obtain a

straight line from the hole of the observation topo to the plumb and

would prolong the line. THIS STRAIGHT LINE WAS THE LINE OF THE MERIDIAN. At a

great distance from the line thus obtained, they marked their "sight",

which at the present time is visible on the hill Quimzachata, in the form of a

white circle which can be distinguished perfectly from the balcony wall of the

Third Period.

In order to determine what degree of accuracy could be obtained in the

determination of the meridian with this ordinary method of observation, we made,

in the year 1928, and in company with one of the astronomers who had come to

Bolivia with the German mission, a similar calculation. We used nothing more

than a tape line, a level and a plumb; for discs we used two empty spools which

we strung on the line and not having a topo de observación at hand, we

improvised one from an empty sardine can, perforating it in the center and

fastening to the side a stick sharpened to a point on the end which we stuck in

the ground.

My companion, stretched on the ground, observed the culmination of

the star and I, following the directions of the improvised "observer",

moved the spools along the line; then we divided in half the distance between

the two spools and from this point (one half of the line) we stretched a

straight line to the center of the improvised topo de observación (the

hole in the tin can); simultaneously with this empirical operation and in order

to test its relative accuracy, we made that same night and on the same

spot a calculation with a theodolite, based on the same star. Comparing both

operations, a slight difference was apparent.

(70)

By repeating these ordinary observations and striking an average for all of

them, one would get an exact calculation. There is not the least doubt that the

priest-astronomers of Tihuanacu, in order to determine their "sight",

made not only one observation, but perhaps hundreds of them. This probably went

on over a long period of years until they were in a position to establish the

"definitive line of the meridian" on a building of the magnitude and

importance of that of Kalasasaya, the stone calendar of the most civilized

inhabitants of the America of that time.

Also, without the direct establishment of the meridian, with which they

would not have obtained the proportion of width and length of the building, the

plan and subsequent construction of the cardinal walls could have been

effected much more advantageously, exclusively on the basis of careful

observations, at each six months of the solstices, or in the following manner.

For an exact observation of the solstices there could have been built on the

site where today the center of the primitive west wall of Kalasasaya of the

Second Period is found, a platform

(71) of relative height, on which they would

have erected the "observation pedestal", (Pl. XV). In order to

determine the solstices from this point they could have made a simple apparatus

more or less in the following form and using only the primitive materials which

they had at hand.

Since they were clever forgers and smelters of bronze they

could have prepared a simple apparatus in the form of a box or cover the size of

the last step of the aforementioned pedestal, over which it would be fastened.

Then almost on the edge of the cover near the observer, there would be bored a

central hole. (Cf. the reconstructed drawing, Fig 16.)

Fig 16

Next on this bronze

cover set on top of the "observation block" with the hole as we have

indicated, they would place a strip of bronze, silver or gold, let us say some

10 cm. wide and 1 cm. thick. This was something less than 73.4 cm. in length,

the diameter of the platform of the pedestal, and both of its ends were pointed,

Fig 17.

Fig 17

Each end of the strip would be drilled so that there could be placed in them the

observation "topos" in a stationary manner. This would be done in such

a way that the one near the observer would pass through the strip about a

centimeter like a spike. The latter would be introduced in the upper hole, or

the hole in the bronze cover, and in this way the strip with its two "topos"

would be free to swing freely on the cover.

In this very simple manner they could have made an apparatus which today we

would call a sight or a diopter.

(72) Its manipulation was extremely simple as

can be seen in fig 18

Fig 18

and looking through the two holes of the "topos"

they would have observed not only the rising of the sun in the solstices, but

also daily and during many years, marking carefully the maximum oscillation of

the sun toward the north and to the south. Thus they would obtain, easily and

simply, an angle which would constitute the total amplitude of the sun between

the two solstices, the vertex of which would be the spike of the first

observation "topo."

Then they would have only to prolong each side of

the maximum angle with lines or sights and on the prolongation of each side of

the angle measure a fixed distance, let us say, eighty "lokas" (the

normal unit of measure of Tihuanacu in the First Period).

(73)

Next connecting

the ends of these two points they would have a line corresponding to the EXACT

MERIDIAN AND AT THE SAME TIME THE PERFECT LINE OR DIRECTION OF THE EAST WALL FOR THE SUN TEMPLE,

their stone calendar, which served to furnish the exact dates of the year to the

dense population of farmers and graziers of Cameloidea who were their

subjects.

Later, to obtain the exact directions of the other three walls, they had only to

strike a right angle at each end of the direction of the east wall already

determined, which in their turn would constitute the lines for the south and

north walls. The west wall was the parallel of the east wall and naturally

intersected mathematically the primitive observation point of the solstices

which was the opening for the first "topo."

This system which we have

just described was, in our opinion, the one which the priest-astronomers

of Tihuanacu could logically have used, and preferably to construct the

Temple of

the Sun, Kalasasaya, in the Second Period. Naturally, this system could

be used

only in the event that to the east there existed a true horizon and not

one

similar to that of the present time which is located some 15 kilometers

away,

(Cf. profile of levels, Vol. I. Pl. I) covering the true horizon and

giving rise

to a false horizon.

Thus it is that looking today from the observation point

toward the northeast corner of Kalasasaya, there is an elevation of 2° 47' and

toward the southeast corner one of 0° 16'. In the long space which separates us

from the construction of the Second Period of Tihuanacu, which is presumed to

be, as will be shown later, from ten to fourteen thousand years, there were, in

our opinion, definite tectonic movements and alluvial accumulations which

undoubtedly could have changed the topography of the high plateau. On the

subject of tectonic changes, we presented a paper in 1931 before the

Twenty-third International Congress of Americanists meeting in New York City

entitled "La remoción del cíngulo climatérico como factor del despueble del

Altiplano y la decadencia de su alta cultura".

On the basis of the

explanations set down in that work, we presume that when they planned to

construct Kalasasaya, there was perhaps an almost free horizon to the east. But

in the case that the present hills extended toward the east at the time of the

Second Period, they still could have constructed the temple in the same place in

an exact mathematical manner, in the following way. With a sight similar to the

one described above --- in a temporary observatory near Tihuanacu --- (for

example the already mentioned one of Lukurmata or one on an island in the lake

where to the east there would have existed an apparently free horizon) they

would make note of the solar amplitude and mark the angle on the metallic plate

underneath the sight.

Later, on the spot where they wished to construct the

"east wall", they would determine the line of the meridian and from

the middle of this line they would strike a perpendicular. At the distance that

they believed fitting for the size of the building they would set on the

perpendicular line the observation point, and on it the sight with the angle of

amplitude brought from the temporary observatory, and they would prolong the

sides of the angle until they struck the line of the meridian. Of course,

previously they would have divided the angle of solar amplitude in the middle

and then would proceed in the manner described above for the plan of Kalasasaya.

Carrying out this operation, as without doubt they must have done, the people of

Tihuanacu were the first to observe the obliquity of the ecliptic. Thus, without

question, Kalasasaya must have been constructed, using one or the other of the

systems which we have studied and described. Kalasasaya being divided

longitudinally into equal parts and, of course, also the angle of solar

amplitude, they believed likewise that they had divided the year into four equal

parts. This belief proved to be erroneous and later they had to rectify it, as

we shall see subsequently when we consider the great monolithic perron which, in

the east wall, gives access to the Temple of the Sun.

Another problem presents itself: after various careful triangulations carried

out in the interior of the great enclosure of Kalasasaya, we discovered that the

angles of its four corners were not completely right at the present time. Those

of the southeast and northwest are somewhat acute while those of the northeast

and southwest are slightly obtuse. We transcribe herewith the measurements of

these angles made by Professor Arnold Kohlschütter, Dr. Rolf Müller and the

author.

Angles of the Corners of Kalasasaya

| Southwest |

Southeast |

Northeast |

Northwest |

Observer |

|

|

|

|

|

| 90° 19' |

------- |

------- |

------- |

Müller |

| 90° 29' |

89° 29' |

90° 27' |

89° 36' |

Kohlschütter |

| 90° 19' |

89° 37'

13" |

90° 20' 41" |

89° 43' 5" |

Posnansky |

The lack of rectitude in these angles

causes the east wall not to be orientated on the meridian at the present time

and gives it a deviation of 1° 1' 30"; that of the west shows a deviation

of 1° 6' 30". The north and south walls, instead of being orientated

mathematically in a north-south direction, show deviations. The north wall shows

a deviation of 40' and the south 42'. The verification of the German Mission is

as follows:

| South Wall |

West Wall |

North Wall |

East Wall |

Observer |

|

|

|

|

|

| 89° 24' |

358° 55' |

89° 20' |

358° 53' |

Kohlschütter-Becker |

| 89° 12' |

358° 52' |

------- |

359° 4' |

Müller-Posnansky |

| 89° 18' |

358° 53' 30" |

89° 20' |

358° 58' 30" |

AVERAGE |

Dr. Müller believes that this small deviation with the resultant lack of

absolute rectitude in the angles was intentional and he gives the basis for his

opinion in his aforementioned work (Baesler-Archiv).

As far as we are concerned, we believe that Kalasasaya in its time was

correctly and mathematically orientated, not only with relation to the meridian

but in the angles of the corners of the building and that it is not a question

of any error on the part of those conscientious, prehistoric architects and

astronomers.

This seems logical, for a native mason draws right angles today

using the systems employed by architects and builders with a maximum margin of

personal error of 6'. As the basis for this opinion which we have just set down,

the following should be stated. All of the valley of Tihuanacu including the

site where the ruins are located, is composed of sandy clay and represents an

ancient glacial lake bed on the edge of which, without any doubt, Tihuanacu of

the Second and Third Periods was located. (Cf. levels toward Lake Titicaca, Vol.

I, Pl. I).

The builders of Tihuanacu set out to construct that great work

without possessing the knowledge of architecture which man had in later periods,

a knowledge which could be acquired only through the experience of thousands of

years. The architects of those times were as yet unfamiliar with the system of

putting foundations under the buildings and especially under the megalithic

blocks or the lower structure, "the groundwork".

That is to say, to

prepare first a base in the subsoil, rather wide and composed of a compact

concrete of stone or masonry so that the foundations of the building --- which

support all of the weight --- would not sink or get out of level when the

subsoil became damp or moved. Megalithic Tihuanacu has no foundations and if it

did have, its buildings, as solid as any in the history of architecture, would

still be standing today perfectly intact.

(74)

It is a recognized fact that clay soil moves when the humidity penetrates to

some depth in periods of intense and prolonged rain, and especially when steps

are not taken to prevent this by means of paving or some other form of

protection of the soil which will prevent the penetration of water. Naturally,

in locations having but slight declivity, the slipping is scarcely measurable

even after several centuries. If the studious reader will consult the general

map (Vol. I, Pl. III) with its curves of level, he will note that the part of

Kalasasaya which is resting on the hill of Akapana, almost forming a block with

it, is the south wall of this temple, where on this account the slipping, if

such there were, must have been negligible.

Thus, this wall shows a deviation of

only 42' from the cardinal east-west line. The same is true of its parallel

which to the north has a deviation of only 40'. As for the east and west walls,

they have deviations of 1° 1' 30" and 1° 6' 30", respectively. This

data could not be more eloquent. The south wall has remained, being connected to

the hill Akapana, almost in its original position. With regard to the north

wall, it has slipped toward the west, or rather toward the lake, pulling with it

the east and west walls.

Also, some 150 m. to the north of the temple, there extended an arm of the lake

and this in the same way was one of the causes for the slipping of the land in

that direction. But the most obvious proof of the movement which took place in

the subsoil is to be seen in an indisputable manner in the excavation carried

out on the floor of the small semi-subterranean temple of the First Period (Cf.

Vol. I, Pl. VII). Here can be seen a drainage canal which has lost its lineal

form through the movement of the subsoil, and is laterally entirely twisted, and

curving.

This temple with its drainage canal (Cf. infra its reconstruction) is built in

the subsoil. After the destruction of the metropolis it was filled with alluvium

and shows perfectly the tectonic disturbances of the lower ground. In that

period the aforementioned canal was straight, well-lined and leveled, with a

small declivity toward the north branch of the lake, so that the rain waters

which fell within the enclosure of the roofless building would run toward it.

Another factor which might have contributed to the loss of rectitude in the

angles of Kalasasaya, could have been the process of shrinking of the strongly

soaked clay soils which contract more where they receive the sun and winds on

one side. In short "to err is human". We shall not be the last to

study the astronomical, geodetical, topographical, geological and stratigraphic

phenomena and problems which today present themselves as indecipherable enigmas

in Kalasasaya. Others will follow, perhaps with more preparation, with more

patience and especially with better instruments, greater time and means, and

they will check our studies and give a definitive verdict in this difficult

material.

Now we shall consider another point of great importance with respect to

Kalasasaya: that of the massive perron which gives access to this significant

and useful monument of American man.

This staircase is not in the center of the east wall of the building as would be

demanded by symmetry and all architectonic standards. Not the slightest

architectural consideration caused the massive staircase to be 1m. 116 mm. to

the north.

Interested for a long time in this problem, the author advanced various vague

opinions and hypotheses in former publications, which of course are superseded

by the present publication. Discussing this knotty problem on various occasions

with Dr. Müller, the opinion of the author of the present work was always that

expressed by Dr. Müller on p. 8 of his study "El Concepto

Astronomico",

or in other words that the perron had to mark a main calendarian point for the

time of the equinoxes. Already at that time the author pointed out that the

deviation of the staircase from the intermediate line of the building of

Kalasasaya must have some relation with the perihelion and the aphelion of the

terrestrial orbit. And thus is the case.

(75)

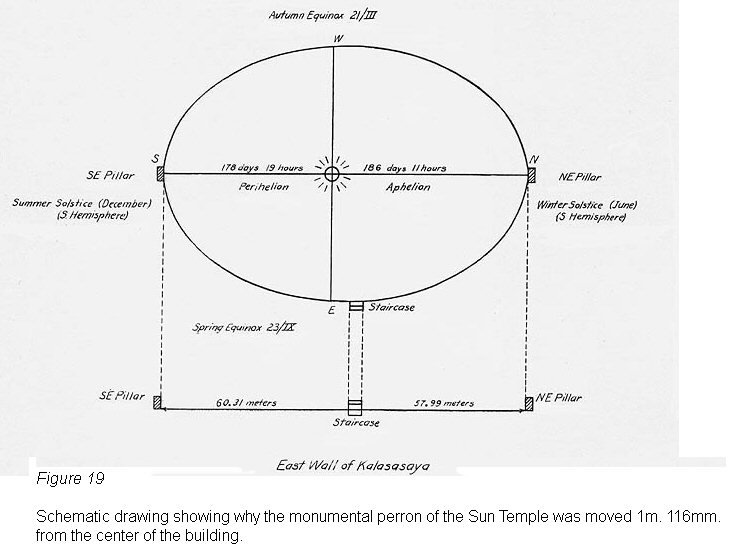

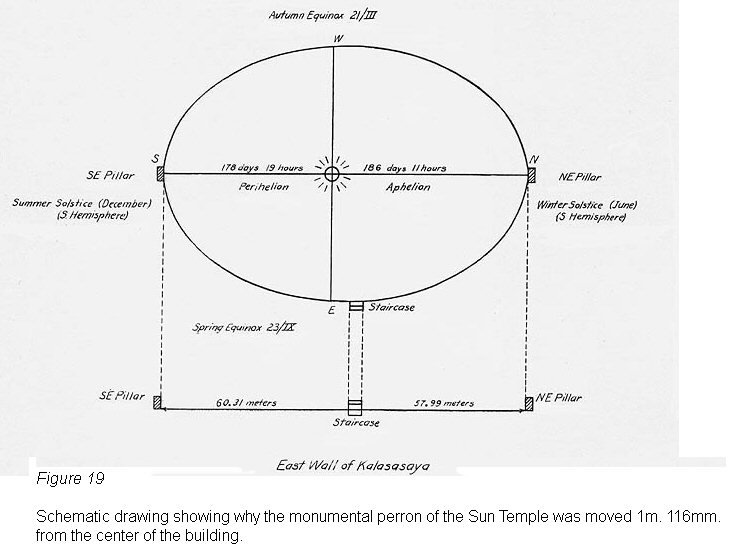

The sun not being in the center of

the orbit but in a center of the eclipse in which the earth turns about the sun (Fig 19)

Fig 19

the earth needs a greater length of time to go from the autumnal

equinox to the winter solstice and return to the vernal equinox than to go from

the vernal equinox to the summer solstice and return to the autumnal equinox.

(76)

That is to say, that for the moving of the earth from the twenty-first of

March (autumnal equinox) to the twenty-third of September (vernal equinox) it

needs 186 days, 11 hours (winter) while to travel from the vernal equinox to the

autumnal equinox it needs only 178 days, 19 hours (summer). Thus there is a difference of 7 days and 16 hours between the winter and summer

semesters. This is the crux of the problem as to why the perron of Tihuanacu is

not in the center of Kalasasaya but is located 1 m. 116 mm. to the north. Let us

explain this in simpler form.

After the priest-astronomers of Tihuanacu had

established --- we may presume with the system of the "topo" sight ---

the northeast and southeast corners (the solstices) of Kalasasaya, and after having

logically divided the angle in half, they thought that they had also divided the

year into four parts. However, in practice they noted the aforementioned fact

that the sun needed more time to go from the north to the center of the building

than from the south to the same place.

Thus, since they wished to divide the

year into four equal parts, they made further observations in order to determine

where the sun would rise at the exact middle of the year, on the twenty-fourth

of March and the twenty-first of September, and they then noted --- surely with

no little surprise --- that the sun did not rise in the center of the temple but

1 m. 116 mm. to the north. With this observation they were

perhaps the first men in the world to note the perihelion and the aphelion, or

the eccentricity of the terrestrial orbit. This difference corresponds for the

21st of September to 1° 0' 56.3" toward the north and for the 24th of

March to 1° 6' 45.3" toward the south.

(77)

This is the way in which they established the point which marked the rising of

the sun at the exact middle of the year as the center of the massive perron.

This, the principal access to the palace, was at the same time a calendarian

point for the determination of the great solar festivals: in Aymara probably

Kjapak-Tokori and in Quechua, Citua-Raymi (for them the twenty-first of

September) (according to Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala: Koya-Raymi).

The

twenty-first of September was the beginning of spring for them, the beginning of

the year, and six months later came the "Willka-Tokori" (in Aymara) or the

Inti-Raymi (in Quechua), the beginning of the autumn, the festival of the harvest (according

to Guaman Porna: Inca-Raymi; making a mistake of a few days he designates it as

"April").

The solstices, the "Willka-kuti"

(78) were

festivals of prayer in which the sun was implored not to go farther away but to

return and favor man with its light and benign heat. These principal

agricultural periods and astronomical seasons gave rise to great festivals and

the determination of their dates was the motive for the construction of the

great Temple of the Sun in the Andes.

Other important dates connected with

agriculture or the raising of cattle were certainly determined by the rising of

the sun over this or that column and were accompanied by their respective

celebrations. Thus, there is almost no doubt that the rising of the sun in the

center of each pillar of the east wall, and later the setting of the sun on the

pillars of the balcony wall to the west, signified important dates in the life

of man of that time.

The west balcony wall which belonged to the SECOND PERIOD, is not in existence

at the present time and we have found only remains of the short corner wall of

the south side. On June 18, 1939, we discovered remains of the north side.

(79)

At the present time, these connect the west wall with the balcony wall of the

Third Period, or they may be the structural prolongations which connect it with

the northwest and southwest pillars of the wall of the Second Period. As we

shall see farther on, only the balcony wall was completely replaced in the Third

Period. Its principal object was to guard the tabernacle of solar observation

and its mysteries from profane eyes.

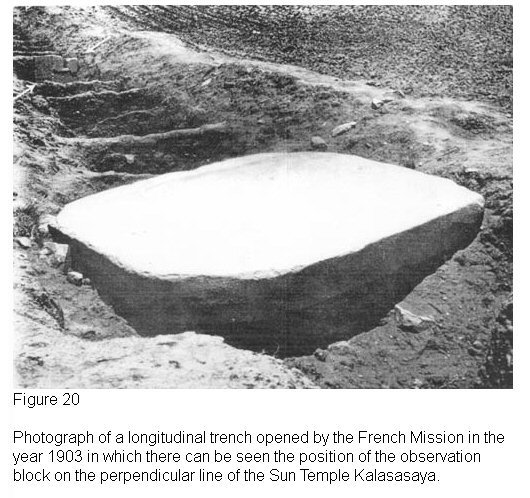

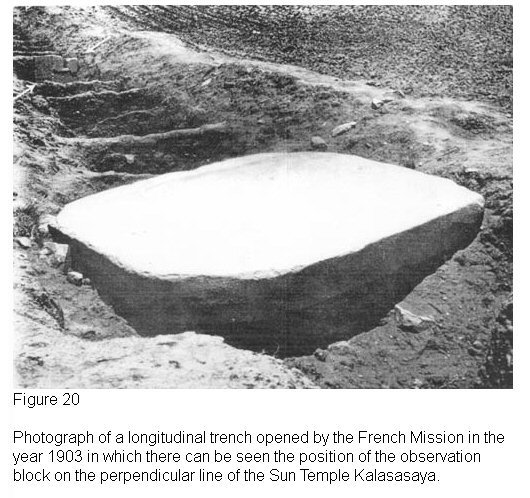

At about two meters from the center of the west wall of the Second Period and on

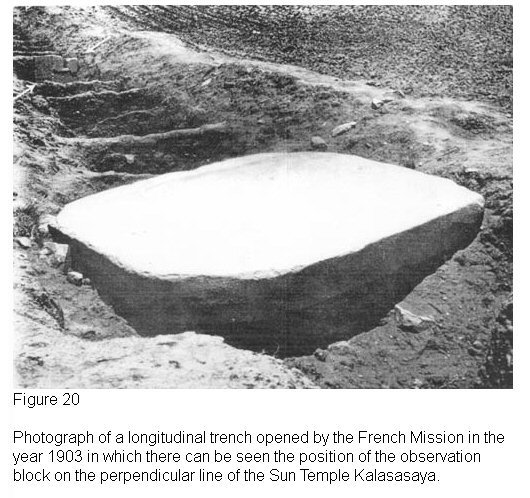

the dividing line of the temple a great slab 2 m. 5 cm. wide, 2 m. 75 cm. long and 25 cm.

thick

(Fig 20).

Fig 20

was found. In our opinion this slab has no

connection at all with the observation point or with its base; it belongs to the

Third Period and later on we shall consider its object. Some 8 m. from the slab

and also on the dividing line of the temple, in the course of the excavations in

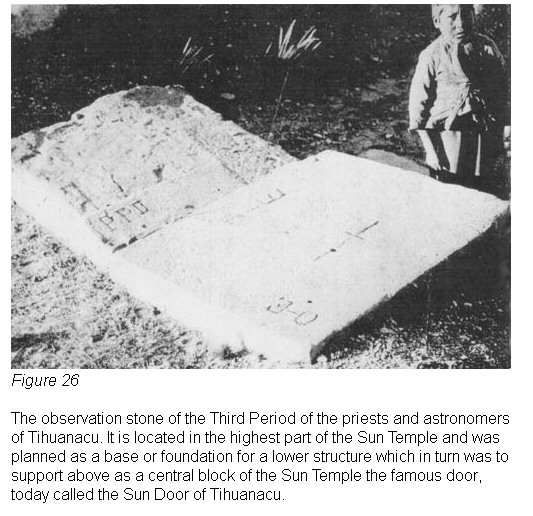

1903, the piece which we have called the "observation pedestal", was

found. In

Fig. 20

it can be seen at the moment of the excavation, still in its

original place, of in the fifth test pit counting from the great slab.

(80)

On

the basis of the material and the technique, it belongs without question to the

Third Period. At the time of the construction of the modern church of Tihuanacu,

it was covered with earth. It was therefore saved from destruction and only

similar blocks of red sandstone found on the surface and supposedly from the

Second Period were used. At the present time they are enchased in the balustrade

of the atrium of the church, (Vol. I, Plate IV a and Plate XIV a). We judge that

these pedestals may have served a purpose similar to that indicated by the

drawing of the sight.

The north and south cardinal walls of Kalasasaya, as can be seen in the

illustrations of Vol. I, Plate XVII a and b, are of red sandstone and at the

present time consist only of a few pilasters --- today showing a very rustic

appearance owing to erosion --- and remains of the same.

Their object at the

time of the construction of the temple was to support the intermediary walls, as

can still be seen perfectly on the south corner of the west wall of the Third

Period (Plate XV a) and on the walls of the temple of the First Period (Vol. I,

Pls. VI and VII) as well as in the remains of the west wall of the Second Period

which were recently excavated. This technique, which we have called "Kalasasaya",

is still in use in rural constructions, especially in fences, throughout Bolivia

and Peru. It is not unusual to see this very old system in all parts.

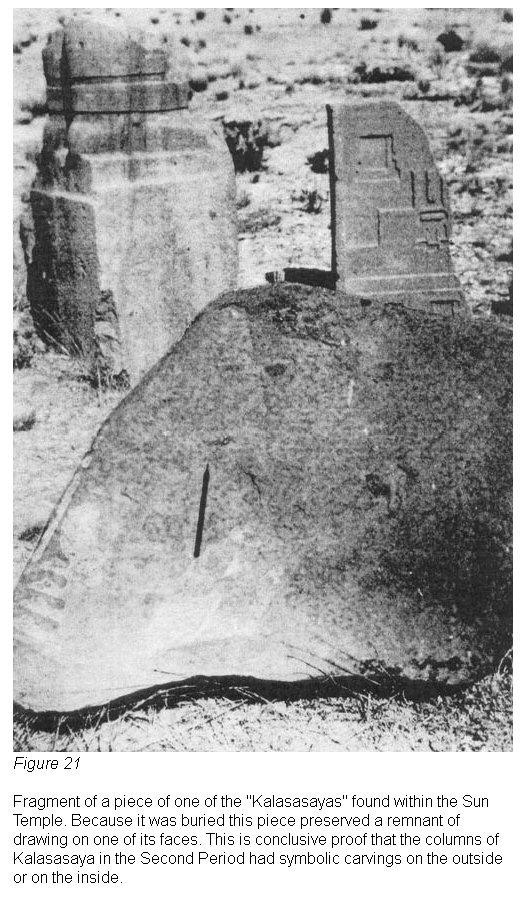

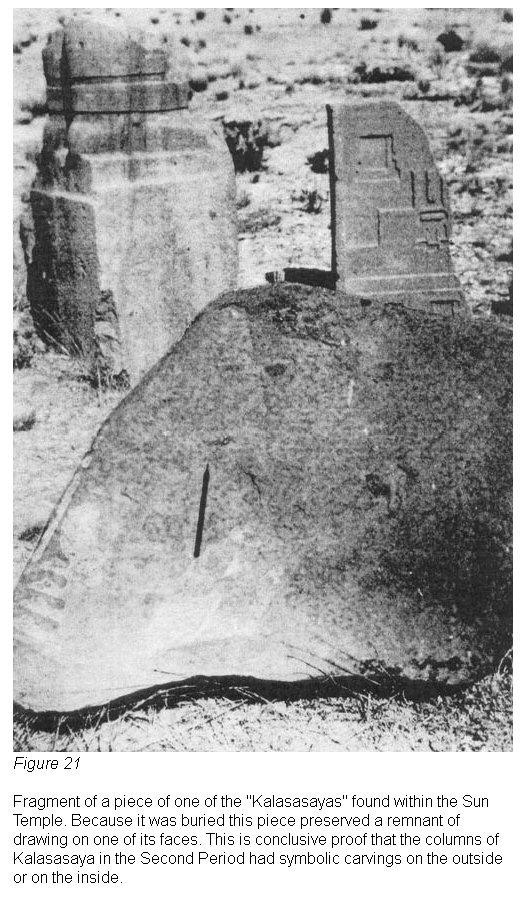

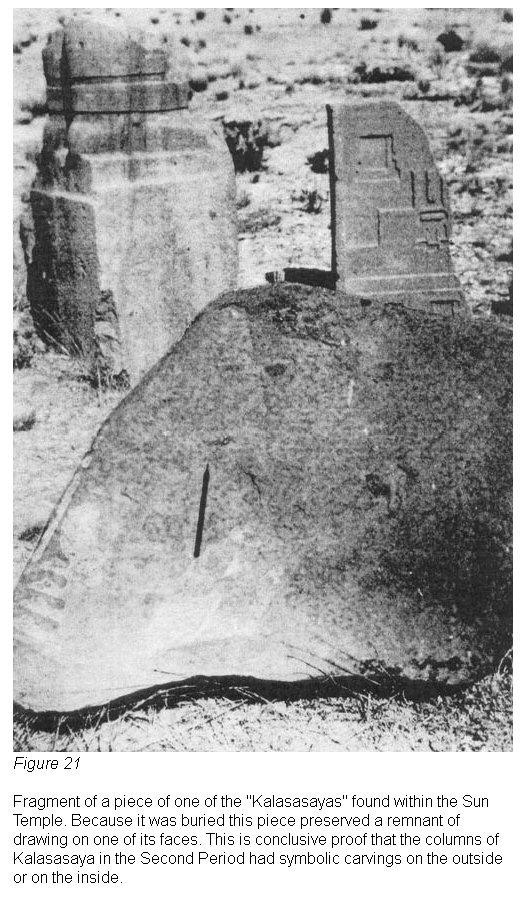

The columns today have the appearance of crude stones planted in the

ground.

However, in their time they were not only carefully aligned and carved

but on

the sides facing the interior of the building were magnificent

symbolical

inscriptions as can be seen on a piece that has fallen from one of them

and on

which a part of these drawings has been miraculously saved,

(Figs. 21

and 21a).

Fig 21

Because of the enormous age of these great pilasters which were the

support of

the walls, some of them have fallen down and others are so thin in

certain parts that they threaten to

fall over from one moment to the next.

At the present time nothing is

being done

to preserve this precious monument which still serves, as it has for

centuries, as a quarry for the inhabitants of the region. Possibly they

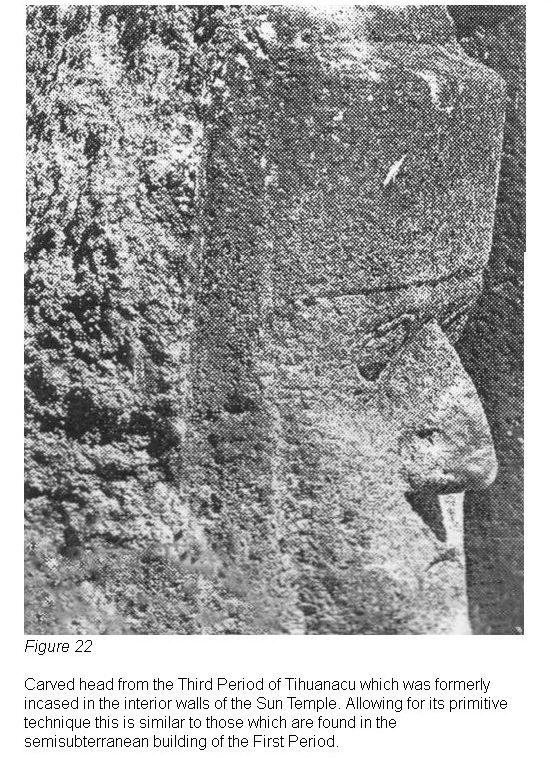

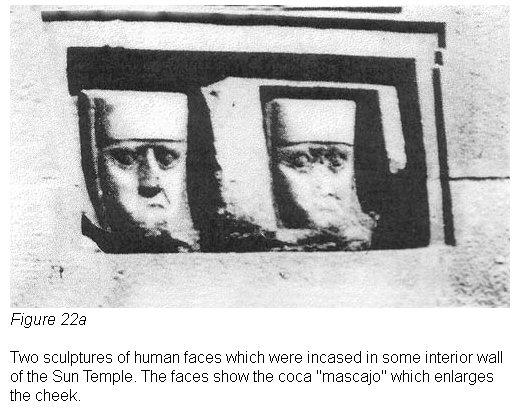

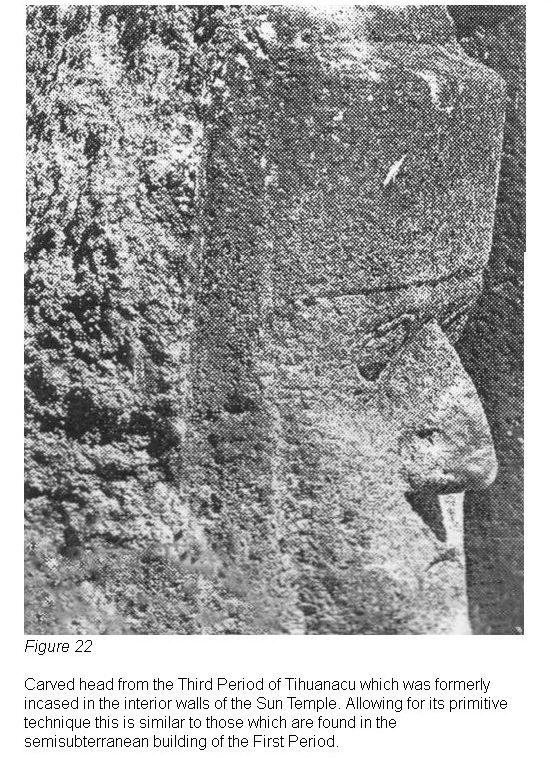

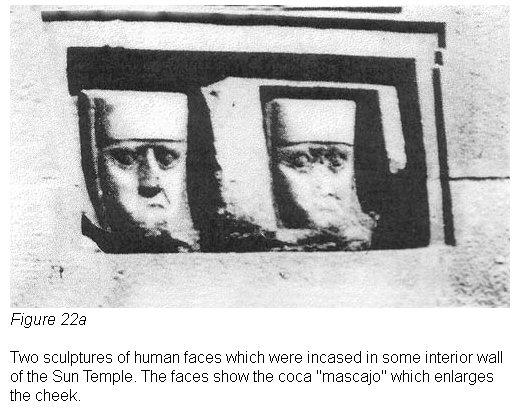

were also enchased with carved human heads, as in the walls of the

temple of the

First Period, (Cf. aforementioned figures). This idea is supported by

the

discovery --- from the Third Period --- of intermediary blocks which

show such

carved heads and in the most perfect technique of that period,

(Fig.

22).

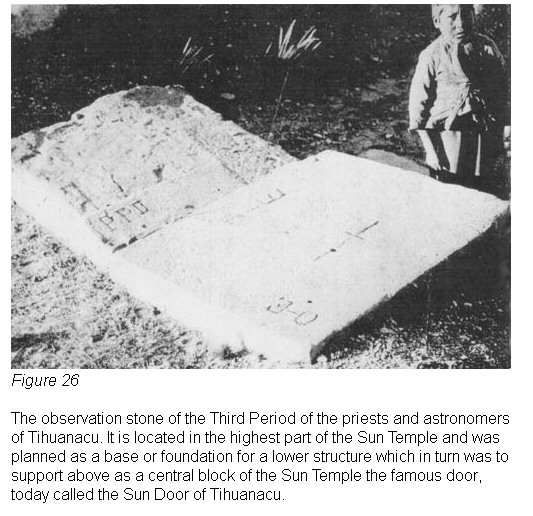

Fig 22

Fig 22a

|

(63) Cf. Posnansky, Antropología y

sociología, Figs. 8 up to 30.

(64) There exist various "Kalasasayas"

on the Altiplano as, for example, in Chiripa, Cumana, Lukurmata, Khonto,

Kaskachi, Merkhetihuanacu and other places.

(65) Jean Baptiste Biot, Recherches

sur I'ancienne astronomic chinoise Paris, 1840.

(66) We have seen a level of Tihuanacu,

taken to London by one Mr. Thomas Richards. (Cf. the corresponding figure, infra.

(Fig. 15.))

(67) Bronze, silver or gold sights in

the form of a flat spoon with a hole in the spoon-shaped part.

(67a) In the Museum of the American

Indian (Haye Foundation), New York City, there are "observation topos"

of silver, the largest of which is 46 cm. long. (Cf Fig. 16a in Vol. III).

(68) R. Müller, op. cit., gives

(according to Wolf) 2100 years B. C. instead of 1100.

(69) Id., gives (according to Wolf) 23°

45' 1" instead of 23° 51' 15".

(70) Dr. Müller in his work "El

Concepto Astronómico del Gran Observatorio Solar Kalasasaya" (Anales de

la Sociedad Científica de Bolivia, Vol. I, p. 6) says: "Out of

curiosity and in company with Prof. Posnansky, we carried out, without using any

instrument, a determination of the meridian based on the culmination of stars

and as a result of that test it was seen that it is possible to obtain good

results by ordinary means by making a number of observations".

(71) Recently, upon building a road in

this locality, remains of foundations were found, possibly from a building used

for observations.

(72) That in the Third Period and

perhaps also in the Second they used and worked bronze perfectly, is obvious

from the large metal bolts with which they joined the gigantic stone blocks in

Puma-Punku and from a great variety of bronze objects found in the excavations.

This apparatus itself might have been made of wood in the beginning, but

naturally this would not have the lasting qualities of bronze for extended

observations.

(73) The "loka" of the First

Period of Tihuanacu was 174 cm. as can be seen clearly in the preglacial

building on the island of Simillake in the Desaguadero River (Cf. Posnansky: Antropología

y sociología andina, 1937). For example the semisubterranean building of

the First Period of Tihuanacu is 2890 cm. wide (16 lokas) and 2600 cm. long (15

"lokas"). Each "loka" of the First Period measures 175 cm.

The building of Simillake has thirty "lokas" of the First Period. With

regard to the "loka" of the Third Period of Tihuanacu it is only

161.51 cm. refer to the balcony wall of Kalasasaya. But in the Second Period, which

has more connection with the First than with the Third, it seems that the "loka"

had the same size of 175 cm. as in the First Period. For example, the width of

the perron of Kalasasaya is 4 "lokas" and that of the sides of the

CONSTITUENT ANGLE of the Kalasasaya of the Second Period has 80 "lokas"

of 175 cm. The change in the size of the "loka" of the First Period of

Tihuanacu is due, in our opinion, to anthropological reasons. The difference in

the arm span (basis of the "loka") of the primitive men of the First

Period, or a length of 13.49 cm., corresponds to the greater physical

development of the man of this period as compared to the man of the Third

Period, more developed intellectually but with a correspondingly reduced

physical development.

(74) Last but not least, if the later

destruction caused by man had not taken place.

(75) Cf. Müller: "Der

Sonnentempel in den Ruinen von Tihuanacu", Baesler Archiv, pp.

132-133.

(76) We are, of course, referring to

the southern hemisphere in which is situated Kalasasaya.

(77) Data for the year 1919.

(78) Cf. Vocabulario of Bertonio,

Spanish-Aymara Volume, p. 436.

Guaman Poma in his Crónica calls the

solstice of June "Huaucay quisqui" and that of December "Inti

Raymi." In support of the supposition that in Cuzco in very ancient times

there were also "sign posts" which marked the sunrise, we note what

Polo de Ondegardo said in his book Los errores y supersticiones de las Indios,

1571 (that is to say, a few years before Guaman Poma began to write his Crónica).

In Ch. 7 he says: "They divided the year into twelve months by the

moons. Already, each moon or month had its marker or pillar around Cuzco, where

the sun arrived that month."

(79) We should point out that this

communication between the balcony wall of the north side of the Third Period

with the west wall of the Second Period was effected in the Third Period as we

proved personally in our excavation carried out the 18th of June, 1939. In this

operation this wall replaced, without any doubt, a previous sandstone wall of

the Second Period.

(80) Test pit of the Crequis de

Montfort Mission, 1903-1904.

|

|

|

|

Back |

|

6. The Approach to Kalasasaya.

The Monumental Perron

|

|

In considering

Kalasasaya of the Second

Period of Tihuanacu, it is necessary to pay particular attention to a

construction of great importance, not only from the astronomic but also from the

monumental point of view. This is the megalithic perron. In the preceding

chapter we pointed out the importance of the center of the perron AS THE

INTERMEDIATE DIVISION OF THE YEAR OF TIHUANACU.

Now we shall concern ourselves

with the details of this magnificent architectural work.

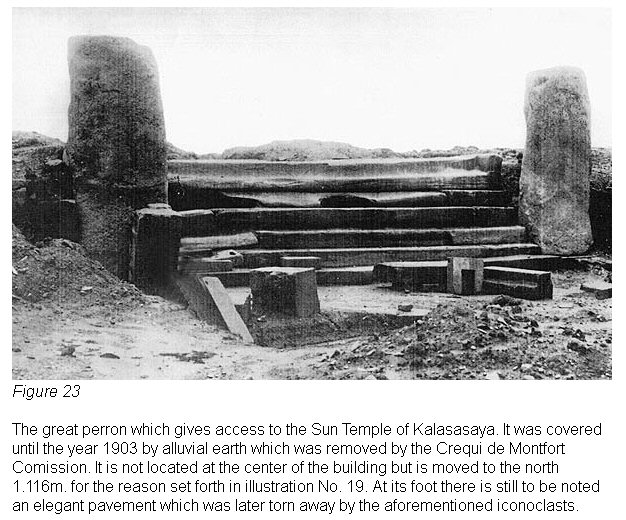

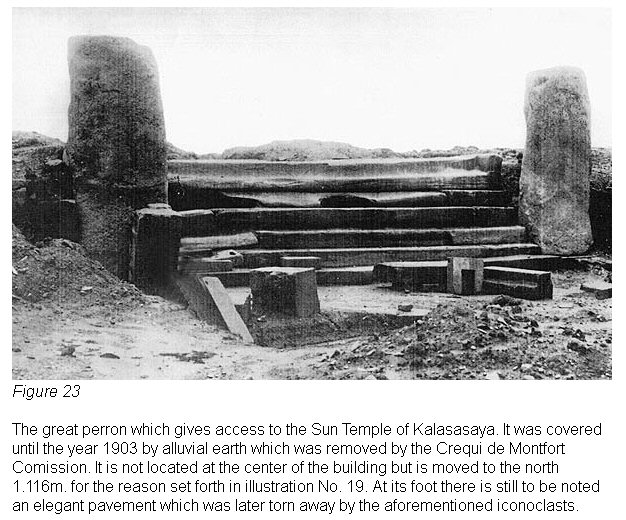

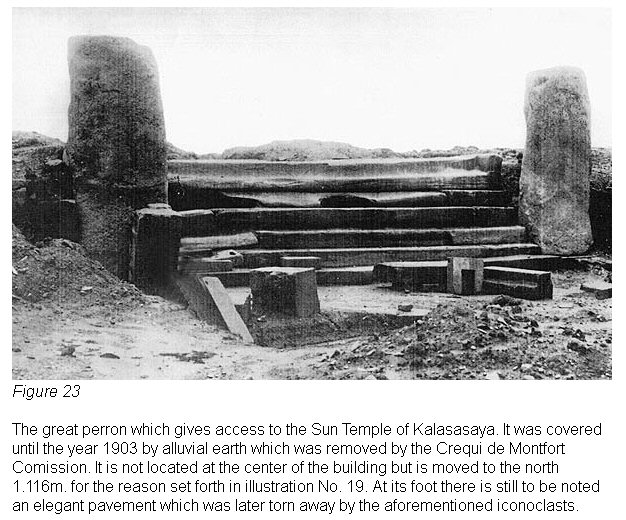

The perron

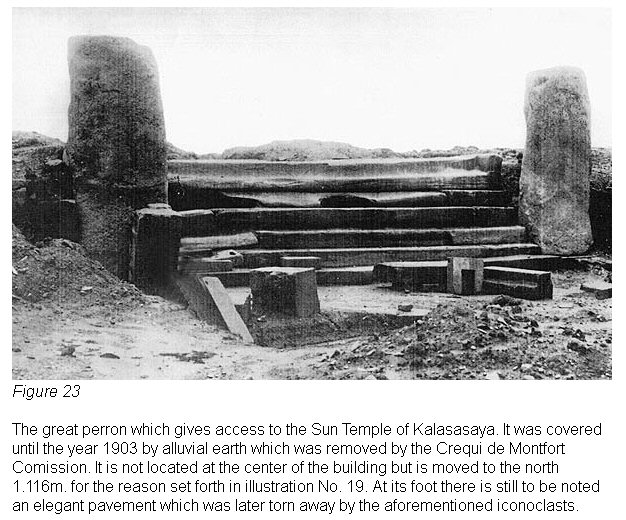

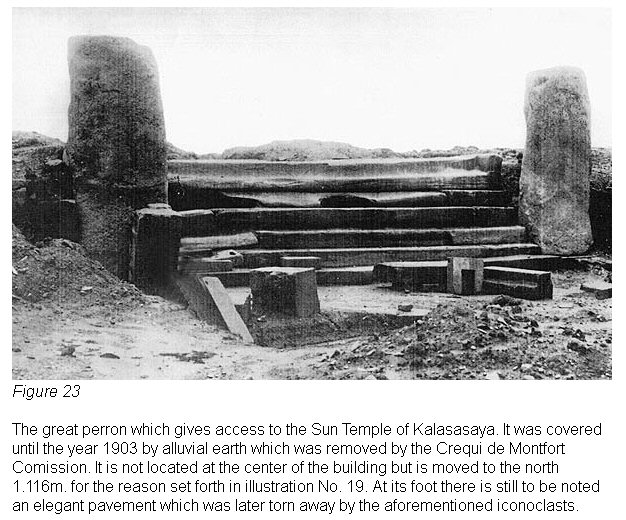

(Fig. 23)

Fig 23

is located as the principal access to Kalasasaya through

the east wall, but it is not in the exact center of that construction. Rather,

it is located one meter, one hundred and sixteen millimeters to the north, for

the reasons set forth in the foregoing chapter.

Bordering it on both sides are

two large pilasters, which lend this architectonic work an even more monumental

aspect. In contrast to the stair, which is of red sandstone, the pilasters are

worked in hard andesitic lava. Comparing their erosion with that of the works of

the Third Period found in the same location, it can be seen that a great space

of time must have transpired between one period and another. We shall consider

this very important point later on, in the study concerned with the age of

Tihuanacu.

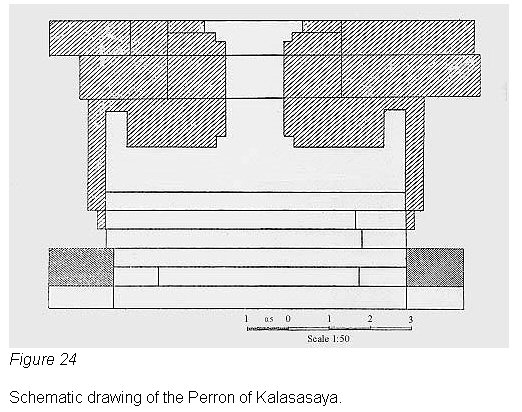

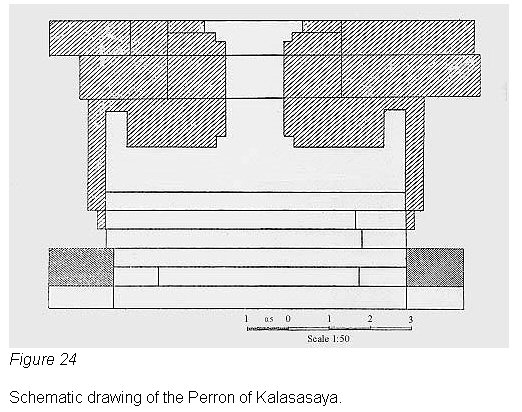

The stair steps, which in the main are composed of monolithic blocks, are seven

in number; the last two on top form the platform and are made of a single piece.

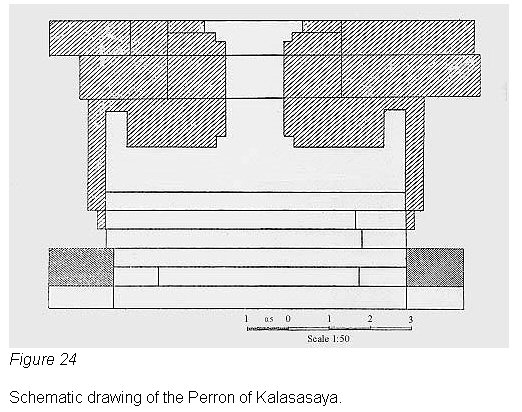

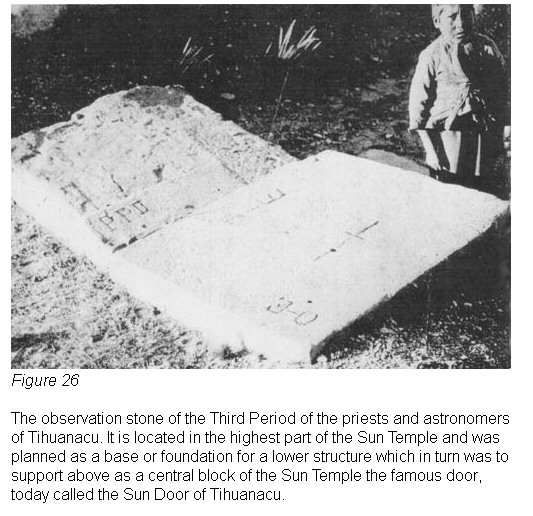

On the top of the platform there is a superstructure as revealed by the

"design made by erosion" in those places where the superstructure does

not extend, (Fig. 24).

Fig 24

Since this place --- shaded in the illustration --- shows

absolutely no erosion from the atmosphere, or let us say from time, it could be

presumed that during the period of the Conquest it carried a part of this

construction on the platform of the stair, and that the blocks which composed it

were used by the perverse destroyer of that epoch in which the church of the

village of Tihuanacu was built.

At the present time we see in relief the material which formed the base of the

superstructure, or of the platform. However, as can be still observed clearly in

the base and pedestals of Puma-Punku, "depressions" must have been

produced in the block of the base where it fitted, or more exactly, the

superstructure was implanted, and only as the result of the erosion of thousands

of years did depressions deeper than the original higher parts finally remain on

the platform of the stair.

The upper construction on the platform was of the strangest type and completely

contrary to our present architecnographic ideas, which would have demanded an

ample entrance to the temple. Consequently, it was not, judging from the

amplitude and magnificence of the perron, designed for the entrance of

magnificent processions or enormous masses of people during the ceremonies and

liturgic celebrations connected with the worship of the sun. Rather, the

entrance was narrow (approximately 1 meter 45 centimeters wide) and possibly

built for very exclusive use. The priests certainly walked through it during the

most solemn moments of the celebration of important proceedings connected with

the mysteries of the Sun Temple.

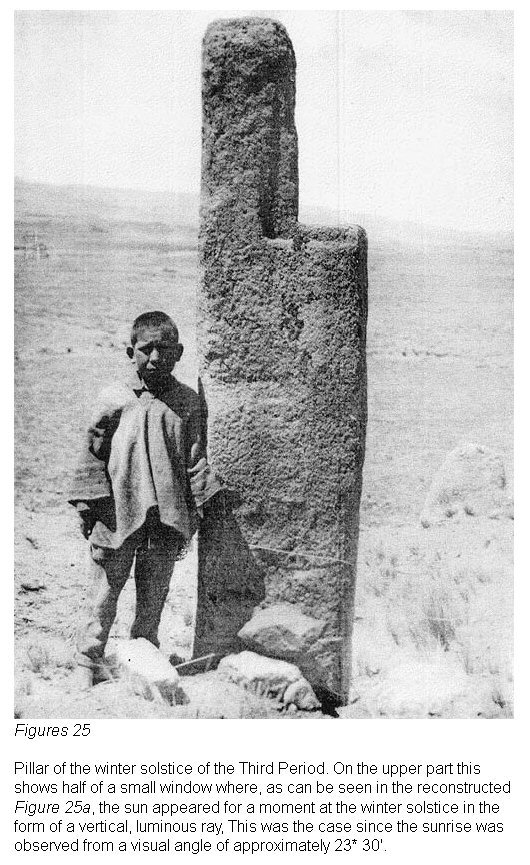

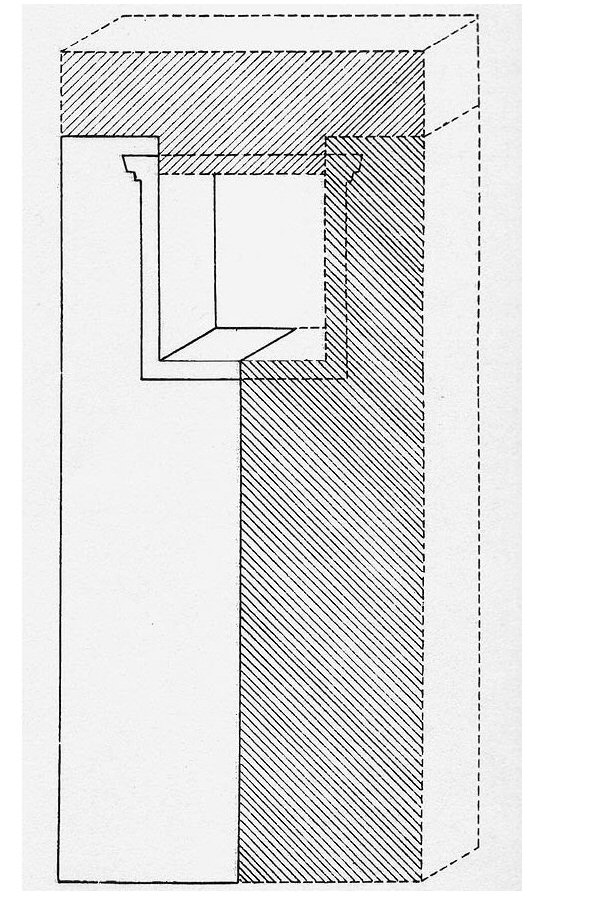

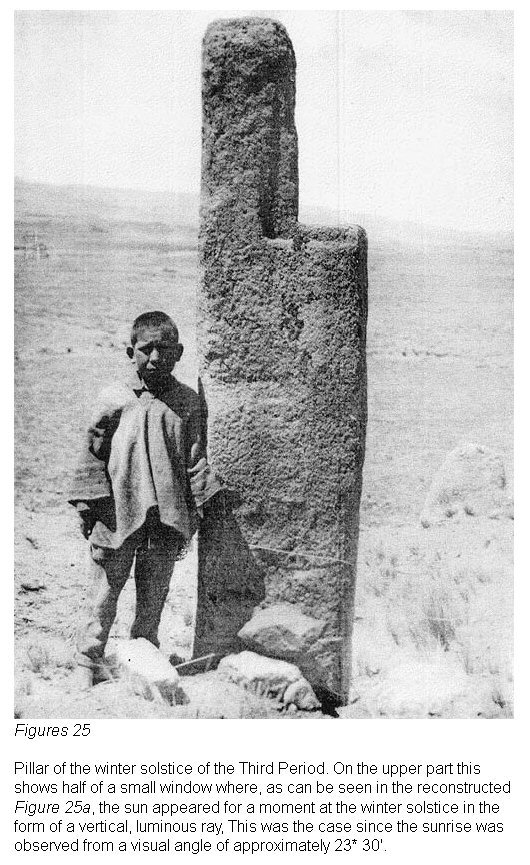

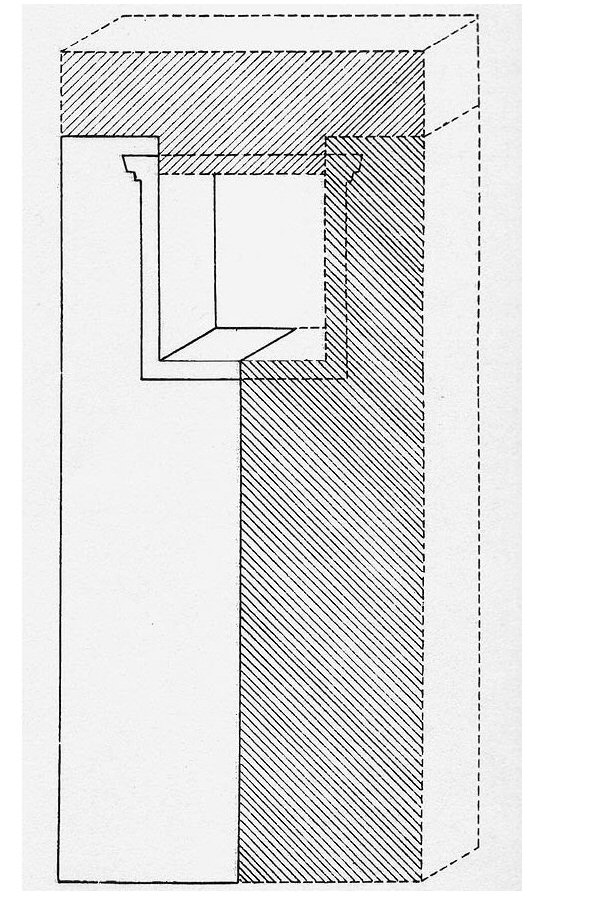

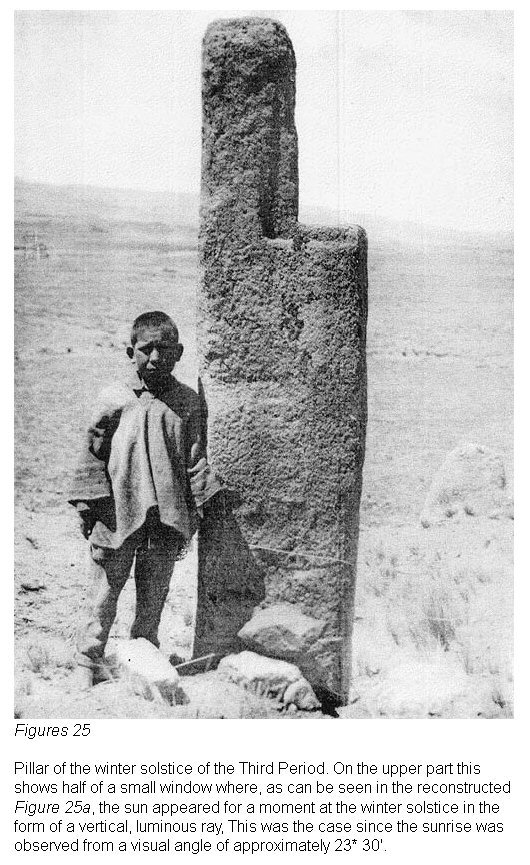

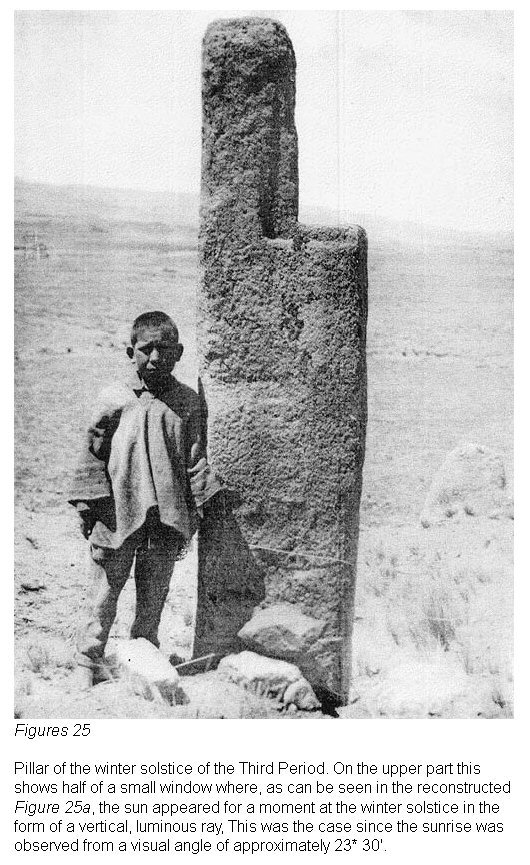

This super construction belongs to the Third Period and was an integral part of

the "sanctissimum" with which it communicated directly, since the

alignment or interior edge of the platform is in line with the external east

wall of the "sanctissimum", on the extreme north end of which is still

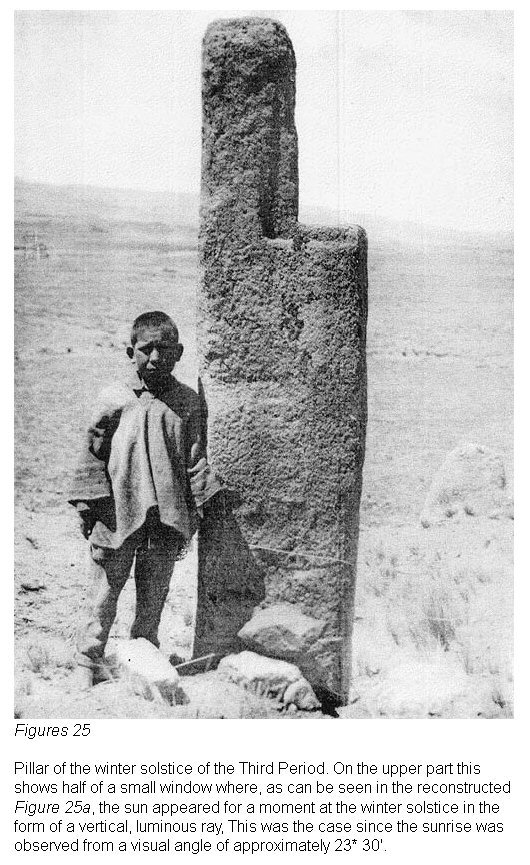

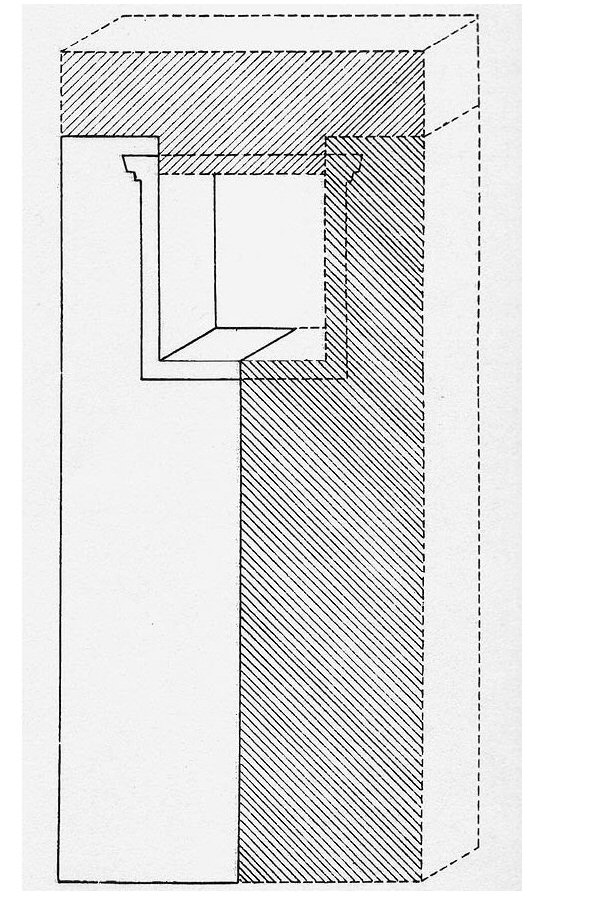

found the pillar of the winter solstice of the Third Period,

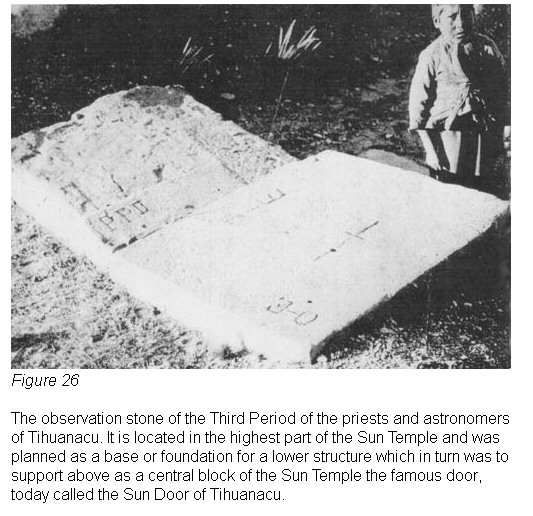

(Fig. 25).

Fig 25 and fig 25a

In

short, although more than ninety percent of Kalasasaya is destroyed, and there

have come down to us only the remains of the building's skeleton, little by

little, and especially when serious reconstructive excavations are carried out,

greater light will be shed on the tangled secret which, until a little while

ago, still covered this famous "Temple of the Sun."

The general map (Pl. III) and other detailed maps inserted in the present work,

show clearly the arrangement and outline of the perron and the astronomical

marks which we have left on the platform for future investigations and

calculations.

|

|

|

|

Back |

7. Kalasasaya of the Third Period

|

|

As was pointed out at the beginning of this chapter, we can see perfectly two

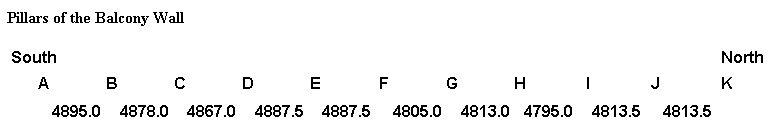

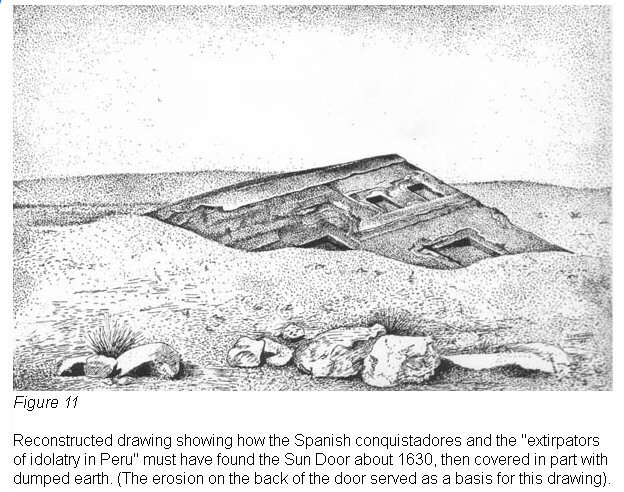

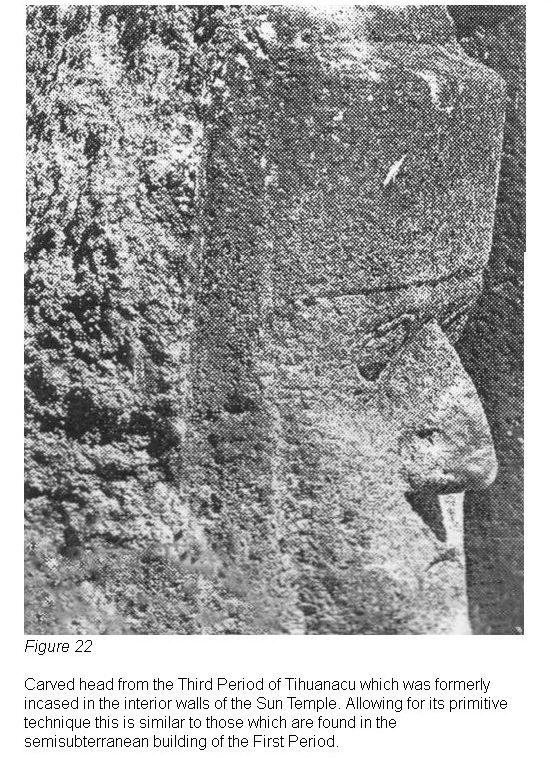

periods of Tihuanacu in the construction of Kalasasaya: the Second and the